Troy Masters was a cheerleader. When my name was called as the Los Angeles Press Club’s Print Journalist of the Year for 2020, Troy leapt out of his seat with a whoop and an almost jazz-hand enthusiasm, thrilled that the mainstream audience attending the Southern California Journalism Awards gala that October night in 2021 recognized the value of the LGBTQ community’s Los Angeles Blade.

That joy has been extinguished. On Wednesday, Dec. 11, after frantic unanswered calls from his sister Tammy late Monday and Tuesday, Troy’s longtime friend and former partner Arturo Jiminez did a wellness check at Troy’s L.A. apartment and found him dead, with his beloved dog Cody quietly alive by his side. The L.A. Coroner determined Troy Masters died by suicide. No note was recovered. He was 63.

Considered smart, charming, committed to LGBTQ people and the LGBTQ press, Troy’s inexplicable suicide shook everyone, even those with whom he sometimes clashed.

Troy’s sister and mother – to whom he was absolutely devoted – are devastated. “We are still trying to navigate our lives without our precious brother/son. I want the world to know that Troy was loved and we always tried to let him know that,” says younger sister Tammy Masters.

Tammy was 16 when she discovered Troy was gay and outed him to their mother. A “busy-body sister,” Tammy picked up the phone at their Tennessee home and heard Troy talking with his college boyfriend. She confronted him and he begged her not to tell.

“Of course, I ran and told Mom,” Tammy says, chuckling during the phone call. “But she – like all mothers – knew it. She knew it from an early age but loved him unconditionally; 1979 was a time [in the Deep South] when this just was not spoken of. But that didn’t stop Mom from being in his corner.”

Mom even marched with Troy in his first Gay Pride Parade in New York City. “Mom said to him, ‘Oh, my! All these handsome men and not one of them has given me a second look! They are too busy checking each other out!” Tammy says, bursting into laughter. “Troy and my mother had that kind of understanding that she would always be there and always have his back!

“As for me,” she continues, “I have lost the brother that I used to fight for in any given situation. And I will continue to honor his cause and lifetime commitment to the rights and freedom for the LGBTQ community!”

Tammy adds: “The outpouring of love has been comforting at this difficult time and we thank all of you!”

No one yet knows why Troy took his life. We may never know. But Troy and I often shared our deeply disturbing bouts with drowning depression. Waves would inexplicitly come upon us, triggered by sadness or an image or a thought we’d let get mangled in our unresolved, inescapable past trauma.

We survived because we shared our pain without judgment or shame. We may have argued – but in this, we trusted each other. We set everything else aside and respectfully, actively listened to the words and the pain within the words.

Listening, Indian philosopher Krishnamurti once said, is an act of love. And we practiced listening. We sought stories that led to laughter. That was the rope ladder out of the dark rabbit hole with its bottomless pit of bullying and endless suffering. Rung by rung, we’d talk and laugh and gripe about our beloved dogs.

I shared my 12 Step mantra when I got clean and sober: I will not drink, use or kill myself one minute at a time. A suicide survivor, I sought help and I urged him to seek help, too, since I was only a loving friend – and sometimes that’s not enough.

(If you need help, please reach out to talk with someone: call or text 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. They also have services in Spanish and for the deaf.)

In 2015, Troy wrote a personal essay for Gay City News about his idyllic childhood in the 1960s with his sister in Nashville, where his stepfather was a prominent musician. The people he met “taught me a lot about having a mission in life.”

During summers, they went to Dothan, Ala., to hang out with his stepfather’s mother, Granny Alabama. But Troy learned about “adult conversation — often filled with derogatory expletives about Blacks and Jews” and felt “my safety there was fragile.”

It was a harsh revelation. “‘Troy is a queer,’ I overheard my stepfather say with energetic disgust to another family member,” Troy wrote. “Even at 13, I understood that my feelings for other boys were supposed to be secret. Now I knew terror. What my stepfather said humiliated me, sending an icy panic through my body that changed my demeanor and ruined my confidence. For the first time in my life, I felt depression and I became painfully shy. Alabama became a place, not of love, not of shelter, not of the magic of family, but of fear.”

At the public pool, “kids would scream, ‘faggot,’ ‘queer,’ ‘chicken,’ ‘homo,’ as they tried to dunk my head under the water. At one point, a big crowd joined in –– including kids I had known all my life –– and I was terrified they were trying to drown me.

“My depression became dangerous and I remember thinking of ways to hurt myself,” Troy wrote.

But Troy Masters — who left home at 17 and graduated from the University of Tennessee at Knoxville — focused on creating a life that prioritized being of service to his own intersectional LGBTQ people. He also practiced compassion and last August, Troy reached out to his dying stepfather. A 45-minute Facetime farewell turned into a lovefest of forgiveness and reconciliation.

Troy discovered his advocacy chops as an ad representative at the daring gay and lesbian activist publication Outweek from 1989 to 1991.

“We had no idea that hiring him would change someone’s life, its trajectory and create a lifelong commitment” to the LGBTQ press, says Outweek’s co-founder and former editor-in-chief Gabriel Rotello, now a TV producer. “He was great – always a pleasure to work with. He had very little drama – and there was a lot of drama at Outweek. It was a tumultuous time and I tended to hire people because of their activism,” including Michelangelo Signorile, Masha Gessen, and Sarah Pettit.

Rotello speculates that because Troy “knew what he was doing” in a difficult profession, he was determined to launch his own publication when Outweek folded. “I’ve always been very happy it happened that way for Troy,” Rotello says. “It was a cool thing.”

Troy and friends launched NYQ, renamed QW, funded by record producer and ACT UP supporter Bill Chafin. QW (QueerWeek) was the first glossy gay and lesbian magazine published in New York City featuring news, culture, and events. It lasted for 18 months until Chafin died of AIDS in 1992 at age 35.

The horrific Second Wave of AIDS was peaking in 1992 but New Yorkers had no gay news source to provide reliable information at the epicenter of the epidemic.

“When my business partner died of AIDS and I had to close shop, I was left hopeless and severely depressed while the epidemic raged around me. I was barely functioning,” Troy told VoyageLA in 2018. “But one day, a friend in Moscow, Masha Gessen, urged me to get off my back and get busy; New York’s LGBT community was suffering an urgent health care crisis, fighting for basic legal rights and against an increase in violence. That, she said, was not nothing and I needed to get back in the game.”

It took Troy about two years to launch the bi-weekly newspaper LGNY (Lesbian and Gay New York) out of his East Village apartment. The newspaper ran from 1994 to 2002 when it was re-launched as Gay City News with Paul Schindler as co-founder and Troy’s editor-in-chief for 20 years.

“We were always in total agreement that the work we were doing was important and that any story we delved into had to be done right,” Schindler wrote in Gay City News.

Though the two “sometimes famously crossed swords,” Troy’s sudden death has special meaning for Schindler. “I will always remember Troy’s sweetness and gentleness. Five days before his death, he texted me birthday wishes with the tag, ‘I hope you get a meaningful spanking today.’ That devilishness stays with me.”

Troy had “very high EI (Emotional Intelligence), Schindler says in a phone call. “He had so much insight into me. It was something he had about a lot of people – what kind of person they were; what they were really saying.”

Troy was also very mischievous. Schindler recounts a time when the two met a very important person in the newspaper business and Troy said something provocative. “I held my breath,” Schindler says. “But it worked. It was an icebreaker. He had the ability to connect quickly.”

The journalistic standard at LGNY and Gay City News was not a question of “objectivity” but fairness. “We’re pro-gay,” Schindler says, quoting Andy Humm. “Our reporting is clear advocacy yet I think we were viewed in New York as an honest broker.”

Schindler thinks Troy’s move to Los Angeles to jump-start his entrepreneurial spirit and reconnect with Arturo, who was already in L.A., was risky. “He was over 50,” Schindler says. “I was surprised and disappointed to lose a colleague – but he was always surprising.”

“In many ways, crossing the continent and starting a print newspaper venture in this digitally obsessed era was a high-wire, counter-intuitive decision,” Troy told VoyageLA. “But I have been relentlessly determined and absolutely confident that my decades of experience make me uniquely positioned to do this.”

Troy launched The Pride L.A. as part of the Mirror Media Group, which publishes the Santa Monica Mirror and other Westside community papers. But on June 12, 2016, the day of the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, Fla., Troy said he found MAGA paraphernalia in a partner’s office. He immediately plotted his exit. On March 10, 2017, Troy and the “internationally respected” Washington Blade announced the launch of the Los Angeles Blade.

In a March 23, 2017 commentary promising a commitment to journalistic excellence, Troy wrote: “We are living in a paradigm shifting moment in real time. You can feel it. Sometimes it’s overwhelming. Sometimes it’s toxic. Sometimes it’s perplexing, even terrifying. On the other hand, sometimes it’s just downright exhilarating. This moment is a profound opportunity to reexamine our roots and jumpstart our passion for full equality.”

Troy tried hard to keep that commitment, including writing a personal essay to illustrate that LGBTQ people are part of the #MeToo movement. In “Ending a Long Silence,” Troy wrote about being raped at 14 or 15 by an Amtrak employee on “The Floridian” traveling from Dothan, Ala., to Nashville.

“What I thought was innocent and flirtatious affection quickly turned sexual and into a full-fledged rape,” Troy wrote. “I panicked as he undressed me, unable to yell out and frozen by fear. I was falling into a deepening shame that was almost like a dissociation, something I found myself doing in moments of childhood stress from that moment on. Occasionally, even now.”

From the personal to the political, Troy Masters tried to inform and inspire LGBTQ people.

Richard Zaldivar, founder and executive director of The Wall Las Memorias Project, enjoyed seeing Troy at President Biden’s Pride party at the White House.

“Just recently he invited us to participate with the LA Blade and other partners to support the LGBTQ forum on Asylum Seekers and Immigrants. He cared about underserved community. He explored LGBTQ who were ignored and forgotten. He wanted to end HIV; help support people living with HIV but most of all, he fought for justice,” Zaldivar says. “I am saddened by his loss. His voice will never be forgotten. We will remember him as an unsung hero. May he rest in peace in the hands of God.”

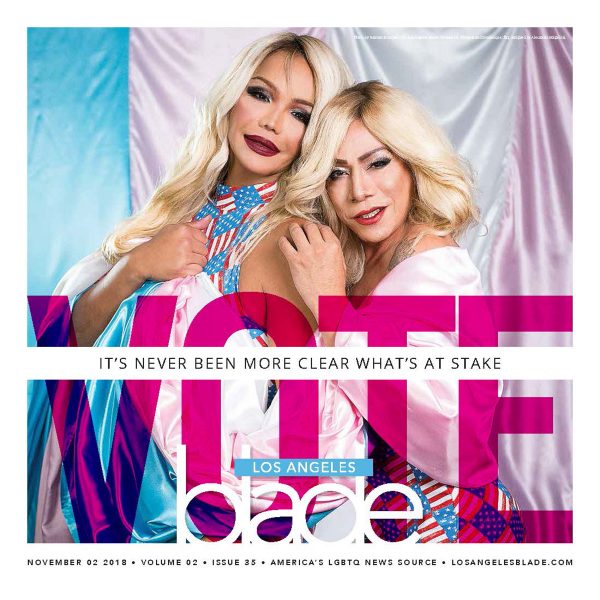

Troy often featured Bamby Salcedo, founder, president/CEO of TransLatina Coalition, and scores of other trans folks. In 2018, Bamby and Maria Roman graced the cover of the Transgender Rock the Vote edition.

“It pains me to know that my dear, beautiful and amazing friend Troy is no longer with us … He always gave me and many people light,” Salcedo says. “I know that we are living in dark times right now and we need to understand that our ancestors and transcestors are the one who are going to walk us through these dark times… See you on the other side, my dear and beautiful sibling in the struggle, Troy Masters.”

“Troy was immensely committed to covering stories from the LGBTQ community. Following his move to Los Angeles from New York, he became dedicated to featuring news from the City of West Hollywood in the Los Angeles Blade and we worked with him for many years,” says Joshua Schare, director of Communications for the City of West Hollywood, who knew Troy for 30 years, starting in 1994 as a college intern at OUT Magazine.

“Like so many of us at the City of West Hollywood and in the region’s LGBTQ community, I will miss him and his day-to-day impact on our community.”

(Photo by Richard Settle for the City of West Hollywood)

“Troy Masters was a visionary, mentor, and advocate; however, the title I most associated with him was friend,” says West Hollywood Mayor John Erickson. “Troy was always a sense of light and working to bring awareness to issues and causes larger than himself. He was an advocate for so many and for me personally, not having him in the world makes it a little less bright. Rest in Power, Troy. We will continue to cause good trouble on your behalf.”

Erickson adjourned the WeHo City Council meeting on Monday in his memory.

Masters launched the Los Angeles Blade with his partners from the Washington Blade, Lynne Brown, Kevin Naff, and Brian Pitts, in 2017.

“Troy’s reputation in New York was well known and respected and we were so excited to start this new venture with him,” says Naff. “His passion and dedication to queer LA will be missed by so many. We will carry on the important work of the Los Angeles Blade — it’s part of his legacy and what he would want.”

AIDS Healthcare Foundation President Michael Weinstein, who collaborated with Troy on many projects, says he was “a champion of many things that are near and dear to our heart,” including “being in the forefront of alerting the community to the dangers of Mpox.”

“All of who he was creates a void that we all must try to fill,” Weinstein says. “His death by suicide reminds us that despite the many gains we have made, we’re not all right a lot of the time. The wounds that LGBT people have experienced throughout our lives are yet to be healed even as we face the political storm clouds ahead that will place even greater burdens on our psyches.”

May the memory and legacy of Troy Masters be a blessing.

Veteran LGBTQ journalist Karen Ocamb served as the news editor and reporter for the Los Angeles Blade.

Source: Washington Blade: LGBTQ News, Politics, LGBTQ Rights, Gay News – www.washingtonblade.com