Brazilian artist Jan Hatchuel You have a knack for making people stop mid-scroll. What at first glance appears to be a feed of sharp photography and unapologetic thirst suddenly reveals itself to be something much larger, a living archive of queer culture stitched together through styling, digital design, and a mischievous sense of humor.

Hatchuel attracted attention with his single. igualthe Rio Pride theme song that featured celebrity cameos from Britney Spears to Demi Lovato, shifted his creative energy to preserving queer history one piece at a time. His page doesn’t read like a portfolio. It looks like a museum that refuses to whisper.

Rethinking the disappeared canon

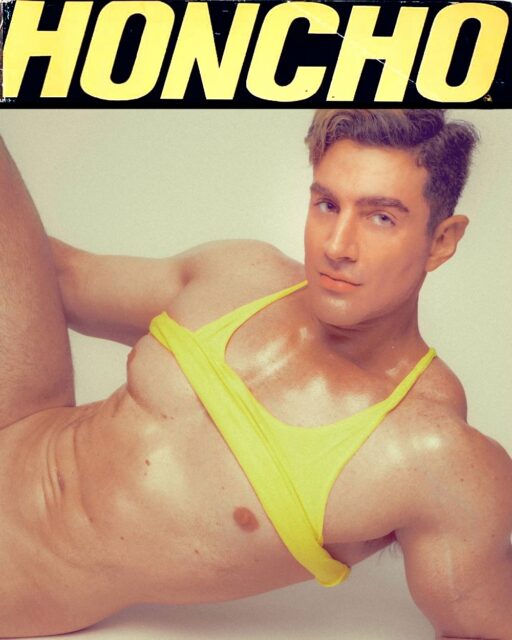

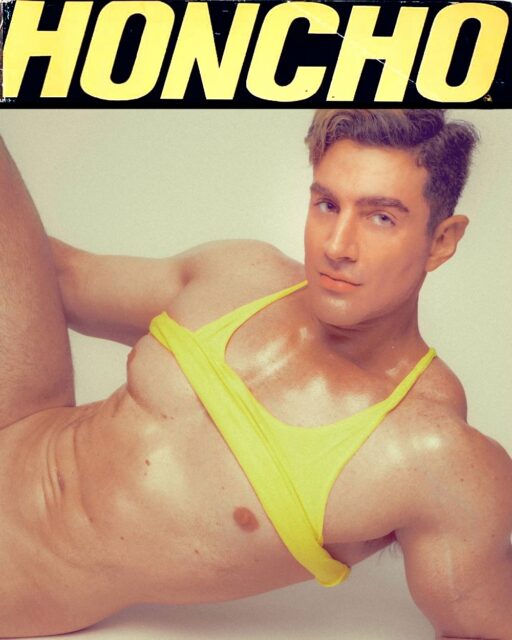

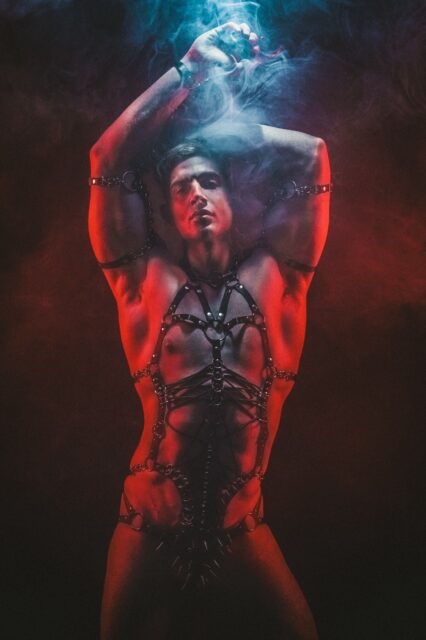

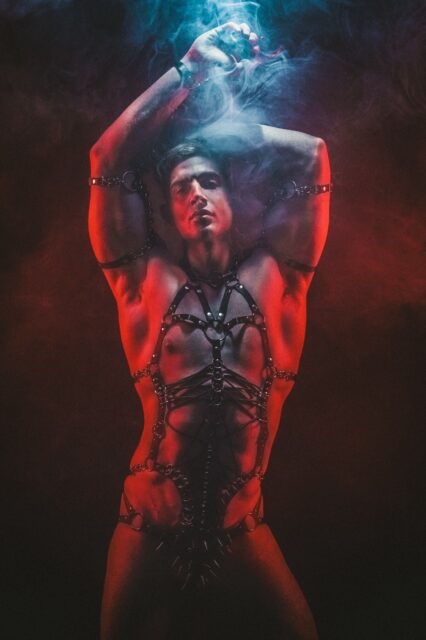

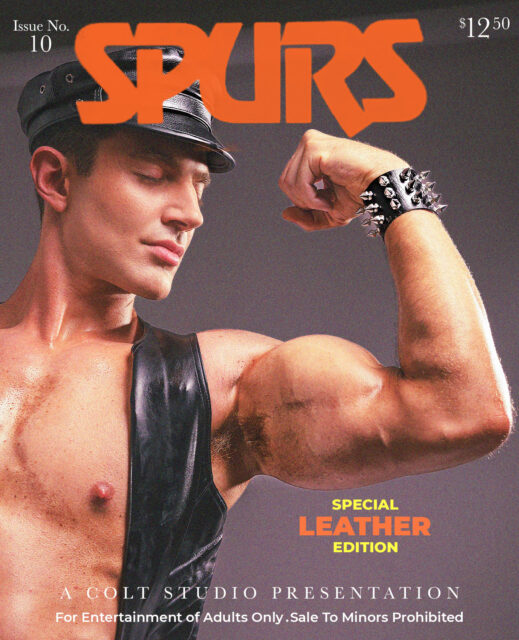

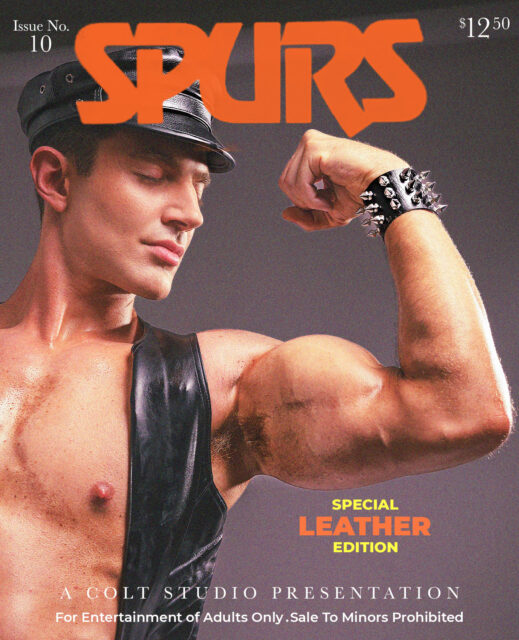

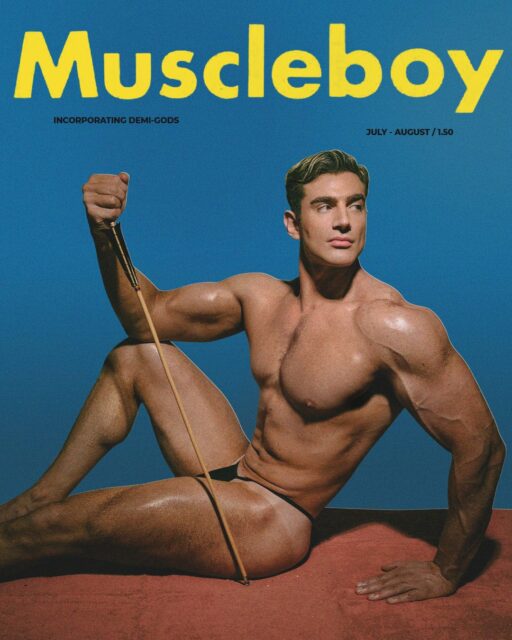

Hatchuel’s feed reimagines the foundations of LGBTQ+ culture. pink daffodil, KereruFinnish Tom, and the erotic subculture that shaped the identity of generations. There’s also a post that revives the cover of an out-of-print queer magazine. Others consider kink, puppy culture, and once marginalized aesthetics.

The motive, he says, is simple. Because too much queer history is hidden in the shadows or fragments are scattered online. “I kept noticing that many defining queer films, artists, and moments weren’t being represented anywhere online, especially not in a way that was fun, sexy, or accessible,” he says. “When someone does a Google search for just one post; pink daffodil Or Tom of Finland, it’s worth it. ”

Sexiness as an educational tool

Hatchuel recognizes that his feed is both archival and erotic, and he embraces that tension. “That balance is completely intentional, and honestly, it’s very important,” he says. “For so many of us, our formative years were defined by repression. Reclaiming sexiness now is not frivolous; it is a radical act of recovery.”

He frames desire as a portal to a less academic and more embodied past. “Our ancestors didn’t just suffer; they lived, they desired, they found joy in each other,” he says. “Sexy makes the past visceral. It tells us that our desires have a pedigree.”

Fighting erasure with visualization

For Hatchuel, the urgency behind this project has to do with how fragile queer documentation is. “Queer history is notoriously fragile and is often erased, burned, or simply left out of textbooks,” he says. “When I refer to works such as; pink daffodil, Kereruor the art of Tom of Finland, I draw from canons created in the shadows. ”

he can see Instagramthis platform is often dominated by ephemeral trends, serving as an unlikely but powerful stronghold for cultural preservation. Young fans often send him messages saying they are learning about these works for the first time. “When young people see things that are dream-like and excessive, pink daffodil “When they feel the hypermasculine joy of Tom of Finland’s paintings, they realize that they have ancestors. It shows the next generation that we have always existed,” he says.

Bringing history back to the city

Hatchuel believes that “accessibility” should not mean “sanitization.” He has no interest in diluting queer culture to fit mainstream brands. “For too long, our history has been shut behind paywalls or softened for mainstream consumption,” he says. “We lose the sweat and chaotic beauty that defined that moment.”

He argues that queer stories belong in the places they were born, in their nightlife, in their community spaces, and now in their social media feeds. “If you only teach the safe version, you’re alienating kids who don’t fit in with the modern world,” he says.

radical revival

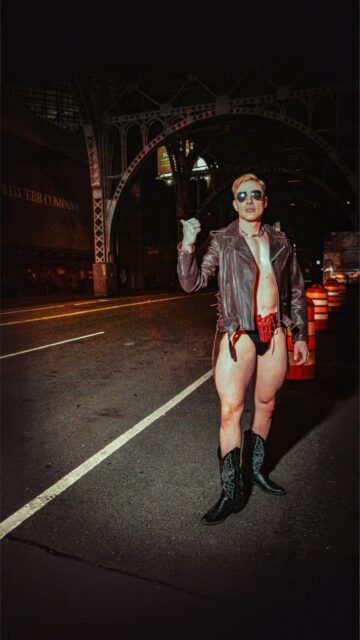

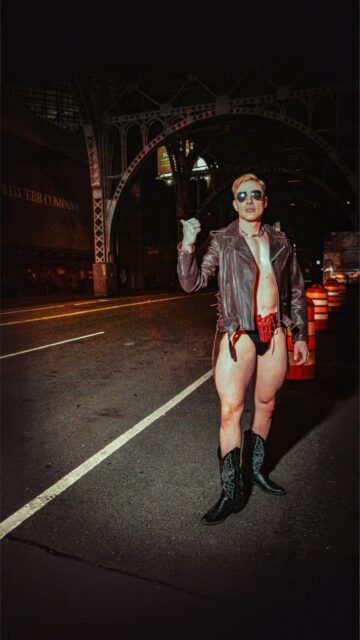

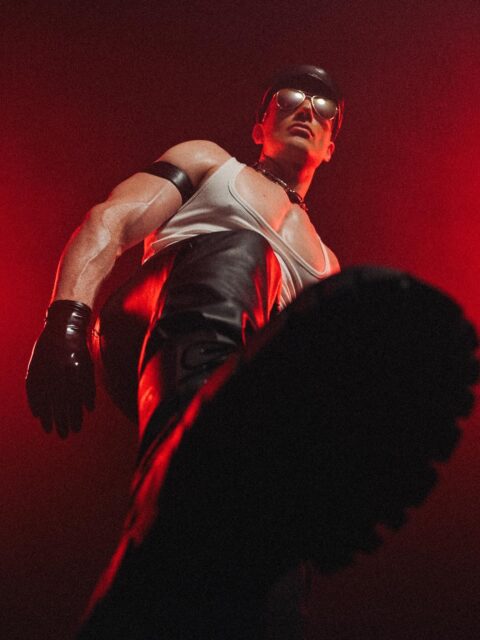

His work often highlights perverted and fetish communities as a legacy rather than a spectacle. Hatchuel would not say why these elements were removed. “The mainstream narrative around LGBTQ+ rights relied on empowerment politics,” he says. “Kink subverts that. It refuses to conform to heteronormativity.”

He is quick to remind people that the leather community helped sustain the response to the AIDS crisis when government systems failed. “Erasing the kinks is detrimental to our survival,” he says. “It’s about negotiation, trust, and freedom from shame.”

A living, breathing time capsule

Hattuel’s Instagram This is part celebration, part protest, and part digital time machine. Although he doesn’t claim to be a historian, his feed offers something that academics often cannot: immediacy. It is a culture preserved with its sweat, humor and desire intact.

“If we don’t organize our history, someone will erase it,” he says.

And in Jan Hatchuel’s hands, queer history is not just remembered, it shines, bends, and refuses to behave.

Source: Gayety – gayety.com