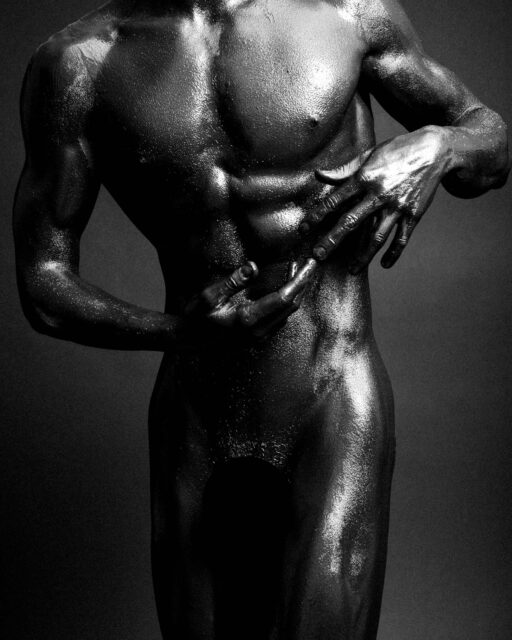

Black and white photography has a way of stripping images down to their emotional core, and in the hands of Ukrainian photographer Dmytro Komisarenko, it’s moving. His portraits do more than just represent the male body, they reimagine it into a supreme form that is mythical, intimate, and slightly unsettling.

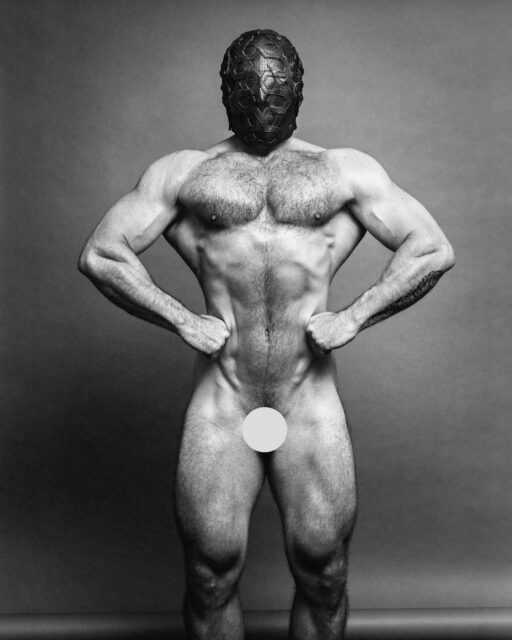

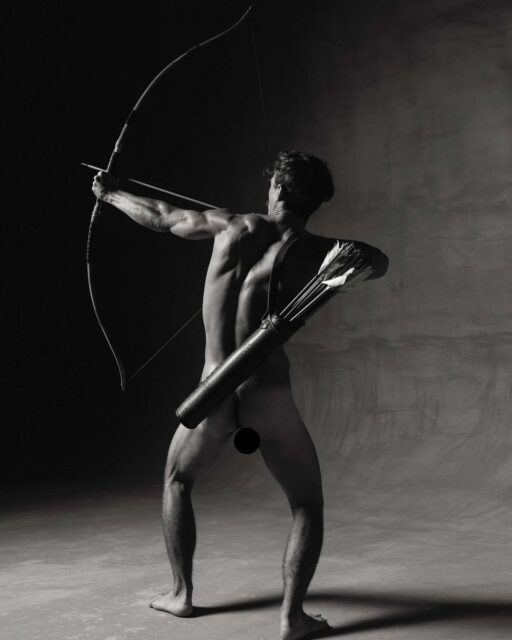

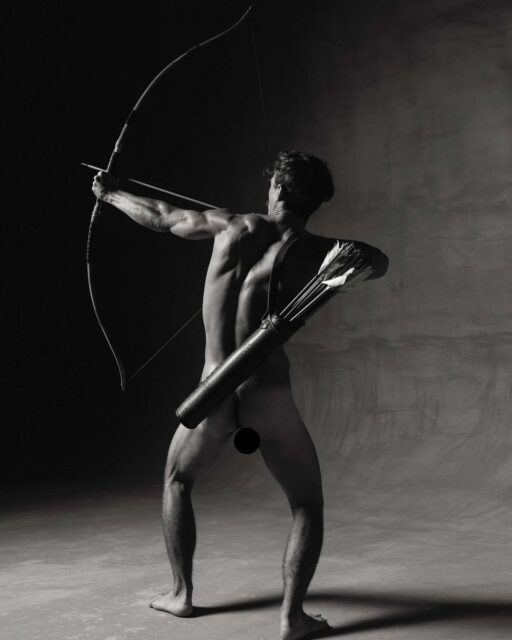

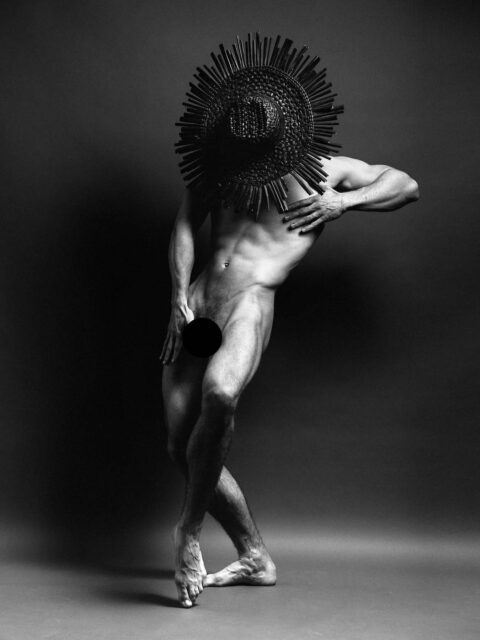

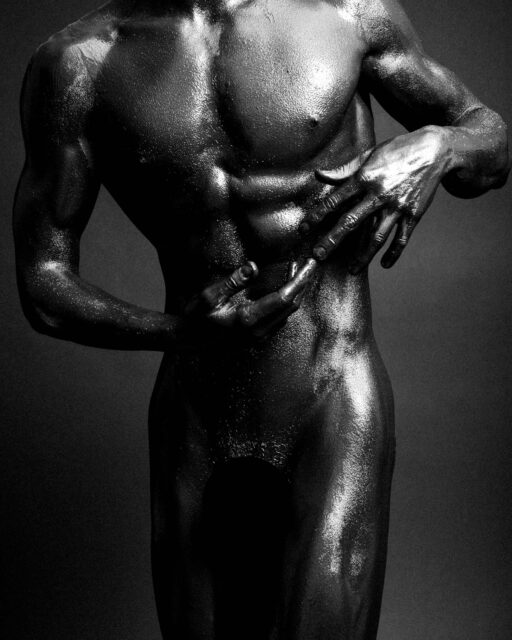

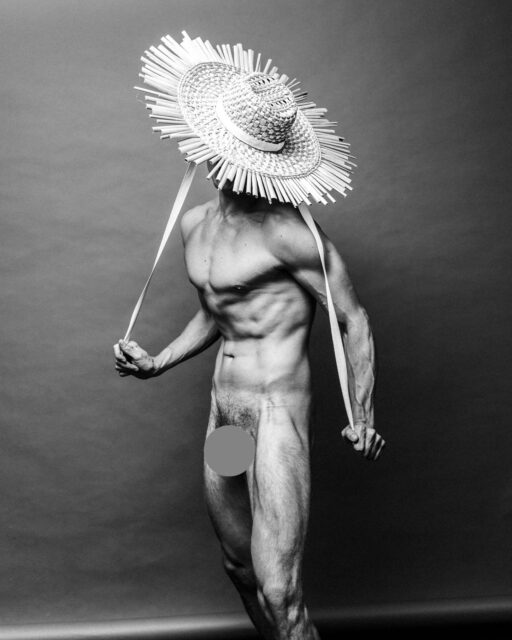

Through this striking series, Komisarenko captures sculptural bodies posed with purpose. Every angle is intentional, emphasizing muscle, tension, and stillness. But what lingers longer than the body itself is the illusion superimposed on it. Masks, headgear, and hidden faces recur throughout the work, pushing the image beyond traditional nude portraiture into something more cinematic.

At times, the numbers feel almost otherworldly. Some headpieces resemble underwater respirators, while others are reminiscent of gas masks pulled from dystopian dreams. The question arises: Are these men human, or are they something more evolved than us? That ambiguity is where this work thrives. You feel drawn into a sci-fi world, even as you feel the unmistakable seduction of the male figure.

From personal history to visual language

Komisarenko’s approach is deeply rooted in introspection. Growing up in Zaporizhia, an industrial city in southeastern Ukraine, he grew up surrounded by cameras. His father’s interest in photography sparked his curiosity from an early age, and Komisarenko was experimenting with equipment long before he imagined photography as a career.

My spontaneous photography led me to start working as a professional photographer. He influenced the likes of Helmut Newton, Bruce Weber and Steven Meisel, but imitation was not the ultimate goal. Instead, Komisarenko developed a visual language that centered on his own inner world, using other bodies as vessels for thought.

That inward focus continued when he moved from Zaporizhia to Dnipropetrovsk and then to Kiev, where his work found an audience open to experimentation. The city gave him the space to explore themes of identity, exposure and concealment without compromise.

The power of hidden things

One of the most fascinating aspects of Komisarenko’s photography is what remains invisible. Often the face is completely covered or cut off. Rather than alienating the viewer, its absence invites projection. The hidden face becomes a stand-in for unspoken emotions, personal fears, or suppressed desires.

In his own words, exposed bodies and ambiguous identities coexist intentionally. Nudity becomes permission and concealment becomes protection. The tension between the two forms meaning.

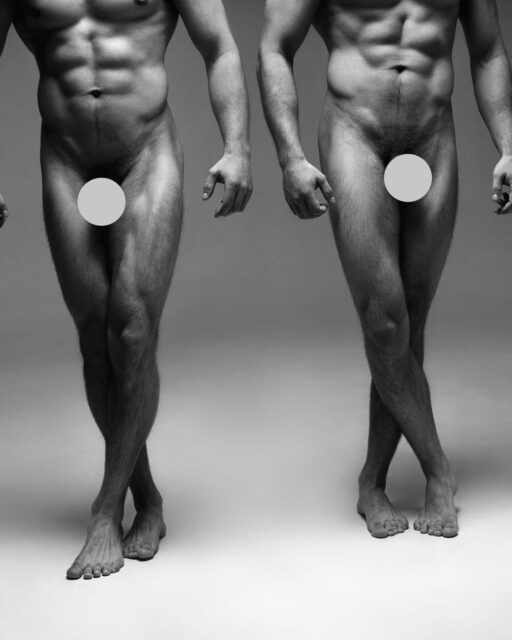

By centering the male nude, a subject that remains policed and misunderstood online, Komisarenko quietly questions who is allowed to be seen and how. His work is not interested in shock for shock’s sake. It asks the viewer to slow down, linger, and assign meaning in their own words.

Art, censorship, and control

Like many artists who work with the human figure, Komisarenko purposefully overcomes censorship across platforms. The public-facing space leads the viewer into a more open space, ultimately reaching a place where the work can exist uncensored. Rather than seeing limitations as obstacles, he treats them as funnels that lead viewers to deeper engagement.

The line between art and pornography, he suggests, depends on the execution, not the body itself. Shape recognition of context, composition, and intent. After all, a naked body is just as provocative as the story that surrounds it.

An invitation, not an answer

Komisarenko does not ask the audience for understanding. His goal is something simpler and more generous: to get attention. If someone can stop, study the frame, and imagine their own meaning, then the piece is a success.

These portraits don’t speak for themselves, but that’s their strength. They are not closed-minded but invite curiosity. In doing so, Komisarenko reminds us that photography is not just what we see, but what we are willing to face when we look at it a little longer.

To see the full gallery and explore more stories like this, visit Gayety’s Substack Are you covered?

Source: Gayety – gayety.com