Alamy

AlamyIt baffled many viewers but pleased critics. We explain why Mulholland Drive, directed by the late David Lynch, came out on top in BBC Culture’s survey to determine the best film of the 21st century.

The film industry at the beginning of the 21st century is experiencing a kind of existential crisis. Terms such as “television-like” or “television-like” were once intended as insults. Now, with the return of television and a new so-called “golden age,” that is no longer the case. So if television has evolved to the point where it is no longer considered an inferior art form, what does this mean for film?

Alamy

AlamyPerhaps the name of the late David Lynch’s heart-pounding mystery drama “Mulholland Drive” BBC Culture Critic Survey In 2016, it was chosen as the best movie of the century. Its roots are in television. The film began as an unsuccessful television pilot and was salvaged into feature format.

The troubled history of Mulholland Drive itself, and the studio politics and power struggles depicted by Lynch within the film itself, hardly seem coincidental. Beneath its dreamlike guise, Mulholland Drive is a masterful commentary on Hollywood intrigue, and it’s inspired, at least in part, by Hollywood’s own woes.

“Backhand Valentine”

The director, who began his career while developing Lynch’s cult TV show Twin Peaks, eventually pitched the idea for Mulholland Drive as a series in 1998. He was given the green light by American cable network ABC, who wanted to replicate the success of the director’s smaller productions. ~ Town mystery series.

ABC was unimpressed, believing that the first episode dragged on at a slow pace and was 37 minutes too long to fit into a traditional television time slot. They also objected to some of the things captured in the filming, including the extreme close-up of dog excrement. In early 2000, Lynch managed to salvage the project by agreeing to make Mulholland Drive into a feature film with double the original budget.

Alamy

AlamyOne of several small, shady characters is the mysterious Mr. Locke (Michael J. Anderson), who appears to control Hollywood from a wheelchair in a shadowy office. One of the plotlines involves an up-and-coming director (Justin Theroux) who is bullied into casting the lead actress with the authority he needs for his new film, but he doesn’t do it.

Injecting Mulholland Drive with a sharp, perhaps pessimistic commentary on Hollywood’s market forces, yet packed with captivating imagery, Lynch has created a package that is highly appealing to critics. They were able to immerse themselves in its dreamlike atmosphere while engaging in intellectual work that deeply criticized the commercial realities of filmmaking. It was a kind of backwards valentine to Tinsel Town.

dream interpretation

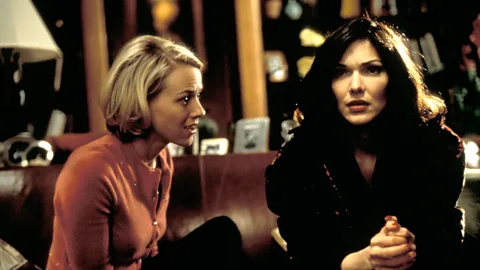

The character closest to the main character in Mulholland Drive is Betty Elms (Naomi Watts), a cheerful aspiring actress who comes to town in search of work. The happy smile would soon disappear from her face. After surviving a car accident, Betty stumbles on Mulholland Drive and meets the dark-haired, doe-eyed beauty Rita (Laura Harring). The experience left her with amnesia.

Alamy

AlamyRita doesn’t know her name. In fact, she started calling herself “Rita” after seeing a poster for the old 1946 Rita Hayworth movie Gilda. Her quest to uncover information about her past takes place among various people, coupled with Betty’s journey to obtain work as an actress. Other stories unfold like a tapestry, some lasting only one or two scenes.

When discussing the most critically acclaimed film of the new millennium to date, perhaps insight can be gained by comparing it to its predecessor’s most critically acclaimed film. A title that repeatedly comes at or near the top of the list is writer-director Orson Welles’ venerable 1941 feature film debut Citizen Kane. BBC Culture’s 2015 Critics Poll. 100 great american movies Put Kane in first place.

If Caine can be considered an essay on the basics of filmmaking, it’s a masterclass in technical processes, from montage to deep focus to dissolves to image manipulation. mise en scene – The appeal of Mulholland Drive is more thematic and conceptual. This isn’t about how a great movie can be achieved, it’s about what a great movie can accomplish, and the limitless possibilities of its ideas.

Lynch’s themes are wild and unconventional. Dreams become reality. A crazy thought bubble came to life. This great film by Orson Welles begins with a brief moment of surrealism with a snow globe and the cryptic words “Rosebud” and then goes more straight forward, but Lynch maintains a surreal atmosphere throughout. I’m doing it. In this sense, Mulholland Drive picks up where Citizen Kane left off.

Its dream-like nature gives rise to many confusing and unexplained things that naturally invite interpretation. But as critic Roger Ebert, one of the film’s greatest champions, noticed: “There is no explanation. There may not even be a mystery.”

Alamy

AlamyThis movie is definitely challenging. Interesting plot tangents are cut off like limbs. Characters appear and disappear. Later in the running time, after what appears to be a dream-awakening scene, the protagonist inexplicably transforms from optimistic Betty to a haunted failed actress named Diane.

“There’s no band”

But it’s the small, self-contained moments that linger the longest in the memory, giving the film its mosaic quality. The best part is the famous Club Silencio scene, which really makes the film unforgettable. It’s both a luxurious sensory experience and an introspective exercise in being able to lift the hood of the film and inspect the moving pieces inside.

In this scene, a surreal nightclub host takes the stage. ”No hey banda!“He screams, ‘The band doesn’t exist’. That means all the sounds the audience hears are pre-recorded. They seem real, but they’re illusions. Nevertheless, the audience is impressed. Roy Orbison’s song was beautiful, heartbreaking and captivating until the singer suddenly collapsed and was dragged away.

The effects are thorough and exquisitely off-kilter. Lynch conjures the illusion while recognizing the sleight of hand required to make us believe it. In other words, the magic of dreams is juxtaposed with the magic of movies, one more readily dissectable than the other.

Encouraging the viewer to participate in its analysis, its dissection, is an act that draws critics like moths to the light. There’s something endlessly fascinating about a movie that prioritizes questions over answers, broadening your expectations for what a movie can accomplish while also providing a rich and fulfilling experience with each scene. Perhaps the biggest mystery is how exactly Lynch did it.

This article was originally published in 2016.

If you liked this story, please sign up Essentialist Newsletter – Hand-picked features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox twice a week.

Source: BBC Culture – www.bbc.com