two quills

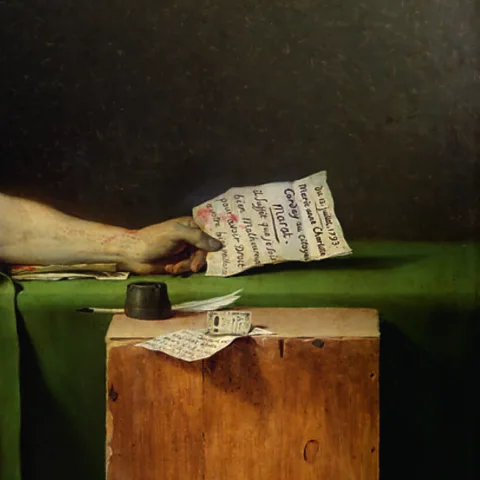

Compounding the friction between the restless fluidity of Marat’s contradictory hands and the brooding stillness is David’s seemingly redundant decision to insert not one but two ink-soaked quills into the stripped-down scene. Marat holds a writing feather, still wet with ink, between the lifeless fingers of his right hand. If you follow its axis upward from the floor, past the white plume, to the upturned wooden box that Marat used as a desk, you will find a second quill lying next to a crouching inkwell. The black nib of this quill points menacingly in the direction of the fatal stab wound, asking the pointed question whether it was the knife or the words that killed Marat. In times of intense politics, it is never clear which is stronger, the pen or the sword. As we will see, in David’s painting the quill and the blade themselves are doppelgangers. They sharpen each other.

two characters

Once detected, the evidence in the painting suddenly multiplies. Lined up in the center of the canvas are not one, but two letters, each written by a different hand. Between the lines of these two documents is the entire plot of the picture. The note that Marat holds in his left hand has been placed by the artist so that it is easy to see how Corday seduced her, without Marat’s knowledge, and took advantage of his benevolent nature. The message is clear. Marat’s kindness killed him.

Marat Assassin/Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium (Brussels)

Marat Assassin/Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium (Brussels)Just below Ms. Corday’s letter, resting unsteadily on the edge of the box, is another letter written by Mr. Marat himself, the document he is believed to have been writing at the time of her attack. This banknote is held down by an appropriation banknote (or revolutionary coin), and scholars believe it to be the first ever depiction of a banknote in Western art. In her letter, Marat selflessly pledged five livres to a friend who had suffered during the revolution, “the mother of five children who lost her husband in defense of her country.” It is said that Marat oozes generosity even in death.

two women

These two letters not only plot an axis of temptation and lies, kindness and redemption, but the story of this painting twists around it. These two letters conjure up ghosts. Two of them are ghosts. The first is Cordez, a scheming assassin who sneaks into Marat’s house with a long knife under his shawl. The second, also invisible, is a distressed widow whom Marat was trying to help, whose husband died fighting for the Republic. Confrontations between female forces, one embodying good and the other evil, have a long tradition in art history. For centuries, artists have staged the struggle between holiness and sinfulness as a fierce competition between strong women. In Renaissance artist Paolo Veronese’s famous Fable of Virtues and Vices (c. 1565), one woman beckons Hercules to honor, while another tempts him to pleasure with a long knife hidden in her back. David updates the fable for the times of revolution. In The Death of Marat, the soul of the nation is at stake.

Source: BBC Culture – www.bbc.com