Aramie

AramieOn March 24, 1944, 76 allied officers broke out from Stalag Luft III, a German prisoner of war camp. In 1977, Raykenyon, a key member of the Escape Team, was interviewed nationwide by the BBC.

On a snowy, moonless night in 1944, over 200 allied officers tried to escape from German prisoners of war. It was the culmination of an incredibly ambitious plan, which entailed production of bribery, tunnels and assembly lines for equipment, uniforms and documents.

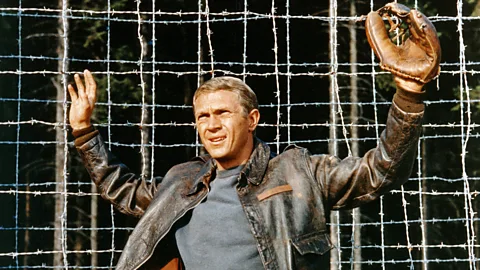

Great Escape, John Sturgis’s 1963 film As for the breakout, it’s a much-loved classic starring Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough and James Garner. But it contains a lot of inaccuracies. Gem Duduk, historian and presenter of the condensed history podcast, explained it in an interview with subway As “a strange mix of creepy creation and pure Hollywood fantasy.”

The story was first told by Paul Brickhill, one of the people who helped with the escape attempt in his 1950 book, The Great Escape. He describes Ray Kenyon, who wrote the book, as the “star forgery” of the mission. In discussions with Dilleys Morgan across the BBC’s 1977 national team, Kenyon said: “It was a good entertainment, but it certainly didn’t represent the real fear of being a prisoner of war. Of course, fear is a personal feeling of being behind a boring wire.

Other former prisoners had different views of the film. Charles Clark, who was in camp at the time, supported the plot as a good look, told the BBC in 2019. Radio Interview: “Even after all these years, I always thought it was what an amazing movie.”

One of the major changes the film made was for the personnel involved. The big escape event actually has almost taken root, but the name has been changed and various people have been combined into the combined characters. At the time of the escape, the Americans were not left in the compound. William Ashdid not participate. The plan was led by Squadron Leader Roger Bushel -Who was renamed Bartlett in the film, played by Attenborough. First captured after being shot down in 1940, Bushel gained a neutral Switzerland within 100 yards and had an impressive record of escape attempts.

Stalag Luft III was a German attempt at escape prevention camps, particularly for air force officers from the UK, Canada, Australia, Poland and other allies. It was built and operated by Luftwaffe and operated as a safe place to hold those who believed to be at risk of escape. But what they weren’t doing was to consider the impact of locking so many escape experts in one place.

A few months of preparation

The camp was built on sandy soil that is difficult to pass through the tunnel. This undersoil is brighter and yellower than the dark topsoil, and is obvious if something appears on the camp ground. The shed sat on his brick legs and revealed the tunnel. Brickhill describes “the height of 9 feet (2.75m) of double bar lead wire fence” in his book. Additionally, the microphone was buried in the ground around the wire, allowing the sound of the tunnel to be picked up.

As expected from the plans that soldiers hatched, the tunneling companies operated with military efficiency. Bushell, also known as “Big X,” was in charge, delegating certain parts of the organization to other men. Plans began even before the Stalag Luft III was built. Bushell and others knew it was coming and volunteered to build it. As a result, they were able to map it and choose the best spot for the tunnel. Bushel had the idea that they would dig three at the same time, not one tunnel. The logic was that if the Germans found one of them, they wouldn’t think there would be two other people. They were to be mentioned only by codenames Tom, Dick and Harry. Bushel threatened anyone in the court even to whom even uttered the word “tunnel.”

Aramie

AramieThe goal was to run away from 200 men. This was a huge effort. Each man needed civilian clothing, counterfeit passes, compasses, food and more. Some passes require photos, so they were smuggled by the security guards who were bailing out by the camera. In the film, the character of Donald Pleasance is in charge of the forgery. The reality is that Kenyon was one of the forgers who had to forge the thousands of documents he needed. In a national interview, he recalled how he made it happen. “We made a printing press for one thing. Each letter had to be carved in the hand from the rubber obtained from the cobbler – a rubber heel – or a small piece of wood cut with a razor blade.” All the documents had to be perfect. They recreated passes and documents that had been stolen from the guard or that they had persuaded them to show them. “7 to 8,000 sheets of paper were made,” he said.

The tunnel itself was also a miracle of engineering and ingenuity. An air pump was made from kit bags and wood, and air was pumped with lines made from empty milk cans sent by the Red Cross. The major problem was the dispersal of excavated soil. So the bag hanging inside the pants was made from long underwear and used to drop sand around camp, where it was kicked to the ground.

Of the three tunnels, Tom was discovered only after a while before the guard was completed. After the break, the decision was made to continue with Harry only. The tunnel ended in the winter of 1943 and was sealed until conditions were suitable for breakouts. It was finally here on the night of March 24th, 1944. A lot was wrong, but in the end, out of the 220 selected, 76 made it before the 77th was discovered by security guards.

A large-scale operation was mobilized to recapture the 76. They all knew they were likely to get caught, but many viewed it as an obligation to try and escape. Another goal for men was to have the Germans draw resources from war efforts, protect them and search them. According to Brickhill, five million Germans were involved in searching for the escaped prisoners. All but three of the 76 have been recaptured. They managed to go to Sweden and the other to Spain.

Hitler hoped that all 73 of the recaptured prisoners would be shot. The people around him managed to speak him – after all, the British were holding German prisoners, and would not kindly take them to the massacre of their officers. Still, Hitler declared that 50 of them should die. Ken Reesea person in the tunnel when it was discovered told on a 2010 BBC Witness History Podcast that people who were murdered were “two and three were taken out and shot.”

He was put to trial

In the fictional version, all men are forced into the field and shot with machine guns, but the reality involved more deceptive measures. Brickhill’s book states that the man was taken to a small group in the direction of his original camp and was shot along the way. He wrote, “The shooting will be explained by the fact that the officer who escaped was shot while trying to escape, or by the fact that he could not prove anything later because he provided resistance.” All the bodies were cremated and, as Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden pointed out in a parliamentary speech given in June 1944, the only reason for this was to hide the way of death.

Bushel was one of the men who were caught and killed. He passed away at the age of 33. Details of his death came up in the investigation. Along with his escape partner, he was shot in the back by a Gestapo officer. His ashes were returned to camp with the rest of the dead, but according to his nie, the cas had been broken when the troops advanced in the camp, so over 80 years later he stayed there.

The two men who could avoid the execution were Jimmy James and Sidney Dows. 2012 documentaryDows gave him a survivor perspective. “It’s rather strange to wonder why you didn’t get shot yourself. That’s what Jimmy and I felt anyway. Why wouldn’t we not be shot.

The executions of 50 prisoners sparked rage in Britain. Eden said in him Speech to Congress: “Therefore, the government under his jealousy must record a strict protest against the actions of these cold-blooded butchers. They will never stop trying to gather evidence to identify all those responsible. They will firmly resolve that these fake criminals are being pursued by the last man when they are evacuated. After the war, great efforts have been made to investigate the murders. As a result, details have been revealed, and 13 Gestapo officers have been hanged part of the executions.

Just six years after his escape in 1950, Brickhill published his account, but was later adopted in a famous film. When Charles Clark was asked about his opinion on the Hollywood version of the event, he said, “Who remembers what a great achievement it was without the film?”

More stories and radio scripts that have not been published so far, in your inbox, History Newslettermeanwhile Required list Twice a week, we offer a handpicked selection of features and insights.

Source: BBC Culture – www.bbc.com