Yun Sun Park/ Getty Images/ BBC

Yun Sun Park/ Getty Images/ BBCIf there’s anything that audiences and awards voters alike love, it’s seeing a faded star revitalise their career with one breathtaking performance. But finding the right role to reannounce yourself to the world is a real art.

Will Demi Moore win the best actress prize at this year’s Oscars? She’s certainly in with a strong chance. Her fearless performance in Coralie Fargeat’s satirical body-horror film, The Substance, has already earned her a Golden Globe. And aside from the quality of her acting, one key factor could tip the balance in her favour: Hollywood loves it when a former superstar makes a comeback – as do we all.

“Hardcore fans of particular actors feel vindicated when they come back into fashion,” says Anna Smith, a film critic and the host of the Girls on Film Podcast, “and more casual fans may still have a certain nostalgic affection for the people they watched on screen when they were younger – all the more so if they starred in mainstream films. And I suspect that deep down, seeing a famous person’s fortunes change for the better gives people hope that it could happen to them, especially in their mature years.”

Mubi

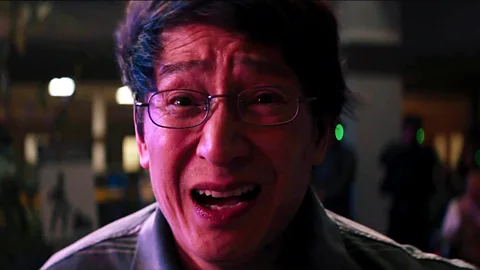

MubiMoore’s current change in fortunes has all the elements that go into an ideal Hollywood comeback. To a lesser extent, the same could be said of Pamela Anderson’s revelatory work in The Last Showgirl, which was released in the US last week, and has garnered its star Golden Globe and Screen Actors Guild nominations. And Ke Huy Quan’s comeback is another textbook case: after abandoning acting for 20 years, the one-time child star won a best supporting actor Oscar for Everything Everywhere All at Once in 2023, and now has his first-ever starring vehicle, Love Hurts, in cinemas in February. As different as they might seem, all three actors are following a pattern that was established decades ago.

“The perfect Hollywood comeback is a carefully orchestrated symphony of narrative parallels and zeitgeist timing,” says Mark Borkowski, a PR expert and the author of The Fame Formula: How Hollywood’s Fixers, Fakers and Star Makers Created the Celebrity Industry. “A sidelined star – like Demi Moore – must step into a role that mirrors their offscreen arc. Add a dash of auteur credibility and just enough edge to provoke chatter, and you’ve got the formula for an A-list resurrection.”

What great comebacks need

As Borkowski says, the first essential ingredient is an inspiring behind-the-scenes redemption story. This Friday marks another major Hollywood “comeback”, with the release of Cameron Diaz’s first film in over 10 years, Netflix’s Back in Action, after announcing her retirement in 2018. However when she left the business, she was still riding high as an A-lister, so her return doesn’t make for a particularly emotional one, particularly when the comeback film in question is a big-budget action comedy which sounds like something she could do in her sleep. It’s mildly intriguing, but nothing more.

Roadside Attractions

Roadside AttractionsBy contrast, Moore’s comeback feels like a timeless fable. She hadn’t starred in a mainstream hit since the 1990s, and, in her acceptance speech at the Golden Globes, she talked about how her confidence had been knocked by a producer labelling her a “popcorn actress”. She was, she said, “at kind of a low point”. But The Substance proved to herself and everyone else that she had more to give. That’s the kind of beating-the-odds, overcoming-the-obstacles arc that Hollywood can get behind.

Most actors’ comebacks have a similar theme: the overdue vindication of someone who was treated unfairly by the industry. Quan was in The Goonies and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom as a boy in the 1980s, but he became disillusioned with acting because there were so few substantial roles for Asian Americans, so when he had the opportunity to shine in Everything Everywhere All at Once, the real-life plot was more satisfying than any fictional one. Viewers and voters could bask in the warm glow of justice being done.

Anderson, meanwhile, has talked about being mistreated within the industry, most recently by Hulu’s Pam & Tommy mini-series, which dramatised her life story without any input from her, so The Last Showgirl has the subtext of someone taking back control of her own persona. To cite another exemplary case, Brendan Fraser’s tour de force in 2022’s The Whale came after years of unemployment and depression which he has linked to his allegation that he was sexually assaulted at a 2003 event by Philip Berk, then president of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, which organises the Golden Globes. His 2023 best actor Oscar win alongside Quan came across as another supremely moving happy ending.

Alamy

AlamyA comeback is even more compelling if the actor’s own experiences are echoed by what’s happening on screen. In The Substance, Moore plays an ex-superstar who has been thrown on the scrapheap – something that she herself knows all about. And such self-referential scenarios crop up again and again in comeback vehicles, from Sunset Boulevard (1950), in which Gloria Swanson played a faded silent film diva, just as she herself was, to the films that revived Bette Davis’s career at two different points, All About Eve (1950) and What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962).

There are plenty of recent examples, too. In The Wrestler (2008), Mickey Rourke is a battered and bruised showbiz has-been. In Birdman (2014), Michael Keaton is an actor who is known for playing a superhero, whether he wants to be or not. In The Last Showgirl, Anderson is a Las Vegas revue dancer whose days in the spotlight are numbered. “A lot of off-screen information seeps into this film,” notes Caryn James in her BBC review – and such information effectively offers audiences a kind of two-for-one deal: as the films skip back and forth across the line between fact and fiction, we’re not just thinking about the characters’ lives, but the actors’, too. “It’s not just acting,” says Borkowski. “It’s mythmaking.”

On the other hand, it’s crucial that these films don’t have the whiff of an ego trip or a vanity project. The message they have to send is that the actors have humbly put themselves at the service of an auteur – preferably, but not always, an auteur who is younger and cooler than they are. In the case of The Substance, it’s Fargeat; in the case of The Last Showgirl, it’s Gia Coppola; in the cases of both The Wrestler and The Whale, it’s Darren Aronofsky.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMatthew McConaughey’s McConaissance began when he signed on for the low-budget likes of Killer Joe (William Friedkin), Magic Mike (Steven Soderbergh) and Mud (Jeff Nichols). Jerry Lewis was Bafta-nominated when he pastiched himself in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (1982). Burt Reynolds was Oscar-nominated for Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997). Sylvester Stallone was Oscar-nominated for Ryan Coogler’s Creed (2015). And this year, Adrien Brody is likely to be Oscar-nominated, too, for his role in The Brutalist. He hasn’t had many memorable starring roles since he won an Oscar for The Pianist in 2003, but by committing to a serious drama from a defiantly independent thirtysomething director, he reminded everyone how magnificent he can be.

Marlon Brando’s comeback with The Godfather is a classic case of a crumbling Hollywood icon being restored by an up-and-coming film-maker. “When it comes to a former A-list star suddenly bursting back into the public consciousness and winning great acclaim, there’s probably no better example,” says Burt Kearns, the author of Marlon Brando: Hollywood Rebel. “By the dawn of the 1970s, the man who was recognised as the greatest screen actor of the 20th Century was literally labelled ‘box office poison’ by executives at Paramount Pictures when his name was floated for the movie version of Mario Puzo’s best-selling book. In late 1970, strapped for cash, he accepted a relatively meagre $50,000 for a month’s work in England on Michael Winner’s low-budget S&M horror flick The Nightcomers.” But after he transformed himself into an ageing Mafia don for Francis Ford Coppola’s film, he won his second Academy Award for best actor.

Alamy

Alamy“A unique twist,” Kearns tells the BBC, “is that 20 years later, Brando had become something of a recluse, only taking occasional cameo roles, when he was convinced by director Andrew Bergman to ‘come back’ as a Mafia boss in The Freshman. Brando agreed, only if he could base the character on Don Corleone. So, in a parody of his landmark role in The Godfather, he was ‘discovered’ once again, surprising critics and audiences alike as a deft comic actor.”

A one-man career reviver

The patron saint of Hollywood comebacks is Quentin Tarantino. And the most significant miracle he ever worked was on John Travolta. By the end of the 1980s, the star of Grease and Saturday Night Fever was reduced to appearing in the Look Who’s Talking films, a series of family comedies in which the thoughts of babies and pets were voiced by actors. The third film in the series, Look Who’s Talking Now, was a box-office bomb in 1993. But less than a year later, Travolta was in cinemas as the black-suited Vincent Vega in Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. An Oscar nomination followed, and he was the coolest man in Tinseltown again.

Not that Travolta was the only beneficiary of this casting: catching fallen stars has been good for Tarantino’s reputation, too. “When he fetches a forgotten or devalued actor from the attic – Travolta, Pam Grier, Robert Forster, Kurt Russell, Don Johnson – I often feel like I’m being somewhat one-upped, as if he were shaming me for not appreciating those folks’ careers and abilities,” says Shawn Levy, the author of biographies of Jerry Lewis, Robert De Niro and Paul Newman, among others. “I don’t think that being their rescuer, as it were, means as much to him as proving that he himself is a savant for loving their undervalued abilities or bodies of work. I picture him scanning his VHS collection and scouring some kind of not-dead-yet website to find performers he can flaunt in future projects.”

What connects all of the films mentioned above is that they allow the actors to demonstrate that they are proper thespians rather than mere celebrities – and that often means shattering their glossy public images by doing something risqué and unglamorous, usually involving sex, drugs and depravity. Travolta is a heroin-addled hitman in Pulp Fiction. Reynolds is a pornographer in Boogie Nights. Birdman has Keaton scurrying around Times Square in his underpants. And The Wrestler has Rourke having cocaine-fuelled sex with a stranger in a grimy barroom toilet. As for The Whale, it opens with Fraser’s character masturbating to pornography and then suffering heart failure in a dingy apartment. His Oscar win was pretty much guaranteed at that very minute.

Alamy

AlamyAll of which brings us back to The Substance. Once the embodiment of red-carpet glamour, Moore is now willing to play someone who is seen as past-it and irrelevant in the film’s early scenes. And in the later scenes… well, we don’t want to spoil anything here, but they are more extreme than anything else in her career so far. It’s no wonder that, even before the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival last May, there were whispers that this was Moore’s “John Travolta in Pulp Fiction” moment. And sure enough, The Substance turned out to have everything a comeback vehicle needs: an actor who has struggled, a role that reminds viewers of those struggles, a bold young writer-director, and material which demonstrates just how far the actor is willing to go for their art.

Now Moore just has to make sure that her “Travolta moment” lasts more than a moment. Travolta, Rourke and Reynolds had their pick of roles after Pulp Fiction, The Wrestler and Boogie Nights, but a few films later they were paying the bills with forgettable thrillers again – and Travolta was making the disastrous Battlefield Earth (2000). Getting back to the top of the Hollywood tree is hard enough – but staying up there is the really tricky part. As Bette Davis and Marlon Brando learnt, one comeback isn’t always enough.

Source: BBC Culture – www.bbc.com