Warner Bros/ Parisa Taghizadeh

Warner Bros/ Parisa TaghizadehFrom its early Germanic roots to Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, the Gothic sensibility has journeyed throughout the centuries, morphing through architecture, art, fashion, music and film.

Few directors are so instantly recognisable by their aesthetic as Tim Burton. Since Beetlejuice became an unlikely hit in 1988, his dark sensitivity and playful, acid palette have captivated audiences. As the film’s sequel is released, Burton still holds a distinctive place in contemporary film-making. The Gothic has inspired him in every sense, from the macabre yet romantic settings of medieval architecture, to the genre’s iconic literary monsters, and emotionally coded fashion of the goth subculture.

Warner Bros. Pictures

Warner Bros. PicturesBurton fuses multiple styles, always with the hero or heroine standing out as proudly goth. In Beetlejuice, Wynona Ryder’s Lydia is marked as the emotionally complex heroine, clothed head-to-toe in black with pale skin and sharp fringe, in contrast with her unfeeling mother who encapsulates 1980s power dressing. Edward Scissorhands, with his buckled black leather and effervescent hair, evokes the 1970s goth-punk scene and the tales of Mary Shelley; his style situates him in conflict with the soft, powdered palette of the 1950s suburbs.

Such characters reflect Burton’s alienation as a child, while connecting in a wider sense with the goth sensibility. “I was just the right age for Beetlejuice to make a deep impression – especially Winona Ryder as Lydia Deetz, and her fabulous goth style,” says Catherine Spooner, professor of literature and culture at Lancaster University, who has written extensively on Gothic culture. “For my 15-year-old goth self, to see a goth girl portrayed sympathetically on screen was incredibly affirming.”

Alamy

AlamyBurton has both informed goth fashion and been inspired by it. He embraces hybridity, in keeping with the gothic journey throughout the centuries, as it has morphed through architecture, art, fashion, music and film. Some trace its origins to the Germanic Gothic army that played a role in the fall of the Roman Empire. Others to the early 12th Century and Abbot Suger’s renovation of the abbey of Saint-Denis in Paris, which borrowed aspects of Romanesque architecture meant to increase height and volume. Subsequent designs of Notre Dame and Westminster Abbey are characterised by rib vaults, flying buttresses and vast arches. The sharply curved features that at first had practical use moved decoratively to doorways, windows, other gothic objects and artworks. Gargoyles created in order to ward off evil spirits brought a tinge of the ghostly to these spiritual sanctuaries.

While later Gothic literature and art has detached from – or subverted – religious ideals, there are clear through-lines from these initial expressions. Cavernous buildings with arched ceilings and hidden spaces remained in works of Gothic literature, conjuring haunting images of the supernatural. There is a romance inherent in these expressions of the Gothic which is still embraced by goth culture, and can be felt through Burton’s narratives. “Gothic literature and art were from the beginning about affect – not just about expressing big emotions such as terror and passion, but also about making the reader or viewer share those feelings,” says Spooner. “It developed a whole repertoire of techniques, from the sublime to the uncanny, to support this. Gothic fashion uses the same techniques and so it is connected to our emotions in a particularly visceral way.”

Alamy

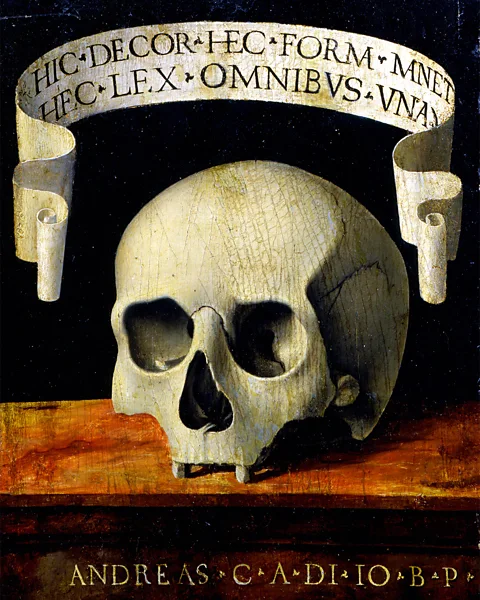

AlamyWhile the fashion of very early Gothic art tended to reflect the time rather than the emotional content of their characters, contemporary goth sensibility can be found in a host of historical paintings. Works such as Andrea Previtali’s Portrait of a Man – Memento Mori (circa 1502) were intended as symbolic reminders of the inevitability of death, often featuring skulls and rotting fruit. Images of witches and demons abound in 18th- and 19th-Century paintings, marrying monstrosity with sublime beauty.

Johann Heinrich Füssli’s 1781 painting The Nightmare depicts a demonic figure on the torso of a woman deep in sleep, draped in a white flowing nightgown, while Albert Joseph Penot’s 1890 work The Bat Woman shows a curvaceous woman with pale skin and dark hair mid-flight, her wings flapping against a turbulent sky. Sir John Everett Millais’ Pre-Raphaelite works contain more subtle Gothic elements: his Ophelia (1853) is cocooned in ornate lace and covered in flowers as she floats upstream; while the doomed lovers in A Huguenot, on St Bartholomew’s Day (1852), one Protestant, one Catholic, are shrouded in swathes of black fabric.

Alamy

AlamyIn the 20th Century, the German Expressionists captured a distinct blend of horror and beauty. The movement inspired the rise of Gothic cinema and, later, Burton. Themes of insanity, chaos and death rage in these paintings, many of which were influenced by the growing world of psychoanalysis, reflecting psychology through external markers such as setting, clothing and lighting. Edvard Munch’s paintings often captured outsider figures. His 1895 Love and Pain (later nicknamed Vampire) depicts an embracing couple; the woman, with pale skin and flowing locks of bright red hair, is draped across a man, dressed in black, with green-tinged skin. Munch’s paintings were drenched in shadow and carried titles such as Jealousy, Anxiety and Despair. His 1893 painting The Scream famously revels in a scene of guttural angst.

More like this:

• Eight of the best Gothic books of all time

Léon Spilliaert captured a similarly cathartic sense of dread in his paintings. His Self-Portrait (1907) depicts the artist in vampiric stiff white collar and large black coat haunted by a gathering of figures, which could be read as dark clothing hanging up or ghostly apparitions. Spilliaert’s Absinthe Drinker (1907) is inherently Burtonesque, with deep rings around her intense round eyes, long dark blue hair, and neck bound with a black scarf and strings of beads.

Moody and romantic

Many of the Surrealists featured moody, romantic fashion in their paintings, especially in connection with occult figures. Leonor Fini’s powerful women are often dressed in flourishes of white lace, thick black feathers, or exuberant silks. Her 1944 depiction of a witch-like Princess Francesca Ruspoli sees the aristocrat dressed head to toe in black, her top covered in long fur and floor-length skirt glimmering in the light. She holds a thin dagger as her jet-black hair swirls into the inky sky. In 1949’s The Angel of Anatomy, Fini does away with clothes, making gothic magic of the human form; the central figure has only flesh on her face, with sinewy muscle and bone exposed on her body. Leonora Carrington likewise embraced the dark magic of Surrealism, with costumes reflecting the bird-like masks of plague doctors; women embellished with black feathers and silk; and ghostly animal-human hybrids.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the second half of the 20th Century, the Gothic found new life in the goth subculture, heavily inspired by musicians such as Siouxsie Sioux and The Cure. This movement continued to weave together internal life with external expression. Visual artists played with these ideas – Penny Slinger’s 1970s series An Exorcism is currently showing at the Richard Saltoun gallery in London, depicting the artist in a decaying mansion subverting bridal and religious clothing with dark romantic aesthetics, while evoking the psychological individuation of her horror-movie-like heroine. Photographers such as Carrie Mae Weems have been categorised as Southern Gothic, addressing the spectres of violence and slavery, while artists including Marina Abramović have embraced the Gothic in works exploring death and spirituality. The Gothic has had a resounding impact on mainstream fashion, with designers such as Rick Owens, Yohji Yamamoto and Alexander McQueen utilising not just sombre aesthetics, but also ideas of rebellion and psychological expression.

Paul Hodkinson, author of Goth: Identity, Style and Subculture, celebrates continued experimentation with the gothic. “What fascinates me is how subcultural styles and more mainstream forms of popular culture can feed off one another,” he tells the BBC. “The original Beetlejuice drew heavily on goth style, but also influenced developments in the goth aesthetic on the ground, with ordinary goths appropriating preferred aspects of the characters and themes, as well as embracing the film itself. There’s always been debate within the subculture about representations of goth in mainstream culture, and it would be problematic to suggest all forms of commercialisation have been positive. But the idea of subcultures as entirely isolated from popular culture is unrealistic. Goth style has been endlessly borrowed from, in cycle upon cycle of art, fashion, film, popular music and more but, equally, the subculture itself has been a developing pastiche of dark-oriented styles drawn from different origins.”

Netflix

NetflixIn the 21st Century, this mercurial force continues to find shape. It can be seen in the visual expression of drag artist Gottmik, with wigs fashioned into devilish black horns or thick monochrome stripes. It morphs through the creative output of Nick Cave, who has transformed from the boyish, goth punk energy of the late 1970s and 80s to the sensitive, labyrinthine grief of his later years – still addressing themes of death and heightened romance. Designers such as Simone Rocha embrace lashings of black lace and silk in their designs. Contemporary art continues to find inspiration in Gothic storytelling. Artists such as Tai Shani explore our relationship with otherness through the monsters of the 19th Century; while Mary Sibande has utilised Gothic supernatural elements to symbolise Apartheid resistance; and Okwui Okpokwasili addresses female sexuality through fusing Gothic literature and West African griot storytelling.

In 2022, Burton’s Wednesday became a role model for many young people rejecting the froth of clichéd girlhood, yet these aesthetics are still seen as a threat – just this month, a school in Texas came under fire for banning all-black outfits, citing concerns over students’ mental health. Beetlejuice and its sequel capture both the sensitivity and chaos of the Gothic, with Michael Keaton’s eponymous character touching on parts that will forever remain outside of societal control. His spectral makeup and iconic monochrome suit evoke not just the rich emotion, but also the hell-raising mayhem that this wayward form of creativity is able to express.

Source: BBC Culture – www.bbc.com