Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection Trust

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection TrustHow Raphael’s rarely seen drawings of the Three Graces reveal the era’s ideas about nakedness, humility, shame, and the artist’s genius. It is part of ‘Drawing the Italian Renaissance’, an exhibition of drawings from 1450 to 1600, held at the King’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace, and is the first of its kind to be exhibited in the UK. It is the largest of its kind.

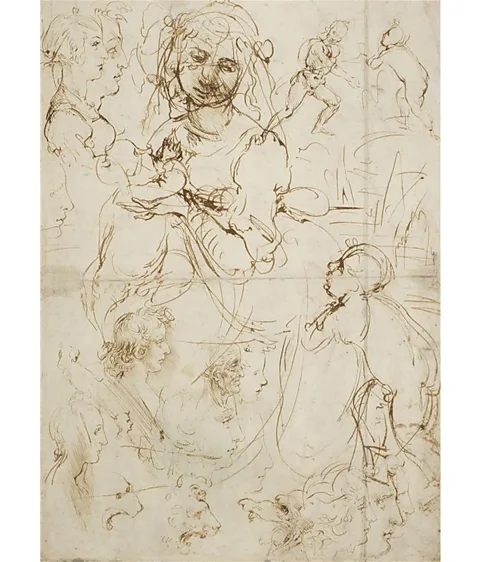

wanderer lobster and sturdy ostrich This is the centerpiece of the 150 chalk, metal point, and ink drawings on display. Depicting the Italian Renaissanceat the King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace. Created by Renaissance giants such as leonardo da vinci, michelangelo, Raphael and Titianoften in preparation for a larger pictorial tableau. royal collection Some were given as gifts during the reign of Charles II in the 17th century. More than 30 of them will be displayed publicly for the first time. Rarely exhibited to the public because of their fragility, these fascinating drawings were just beginning to be recognized as works of art in their own right at the time, but this collection of Italian drawings from 1450 to 1600, previously held in Britain, It constitutes the most extensive exhibition ever held.

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection Trust

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection TrustEven more unusual than these animal studies are drawings of female nudes, which outnumber naked males by a factor of three to one. “The male body is the absolute focus of creativity,” explained a Renaissance historian maya corydiscussed the exhibition on BBC Radio 4’s Front Row in October. “This is a Christian society, and it is the male body, not the female body, made in the image of God.” Leonardo da Vinci Vitruvian human figureA perfect example of ideal proportions. At the time, she said, it was the male physique that was “closest to divine perfection.”

There were also practical issues. Martin Clayton, curator of the exhibition, said: “Artists’ studios would have been male-dominated environments, and if there were no ‘professional models,’ it would be against all social norms for a woman to undress in front of a man other than her husband. It would have been the opposite.” he told the BBC. For example, when Michelangelo needed a female figure, it was a male model who would pose. “This has led to misunderstandings and distortions in the depiction of women’s bodies.”

However, Raphael was the first to resist this trend and based his sketches of female nudes on real-life models. “He was a very practical artist who deftly used drawing to address visual problems and worked very quickly from initial idea to final composition,” says Clayton. The drawings “allow us to see the artist’s immediate reaction to the living figure as he studied pose, proportions, movement, and anatomical details,” he added. In Raphael’s case, “his decisiveness and openness to change and possibilities are at once evident.”

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection Trust

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection TrustRaphael’s Three Graces (c1517-18) is a red chalk work with traces of metal point sketching, revealing the artist’s talent. As he moves one model through three different poses, we witness the meticulous process behind creating a vibrant fresco. Cupid and Psyche’s Wedding Feastthese three figures eventually appear and anoint the newlyweds with future happiness. The complexity of the unclothed human body was the ultimate test of Renaissance artist’s talent, and at the same time satisfied the scientific passions of the time. The woman’s shapely biceps and quadriceps demonstrate the same interest in anatomy seen in Da Vinci’s densely annotated works. leg muscles (c1510-11) is also on display. But there is a softness to the face and abdomen that is missing from the exhibition’s depictions of men. head of youth (c1590) with the muscular jaw of Pietro Facchini or Bartolomeo Passarotti. saint jerome (c. 1580).

ideal of women

looks a lot like Michelangelo davidsculpted ten years ago, Raphael appears to be pursuing an ideal, even as he paints from life. in letter Reportedly written in 1514 to his friend Baldassare Castiglione, he expressed his struggle to capture perfection in real life. “You would have to look at several beauties to picture one beautiful woman,” he wrote. “But I don’t have a lot of judgment and I don’t have many beautiful women, so I’m going to use an idea that comes to mind.”

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection Trust

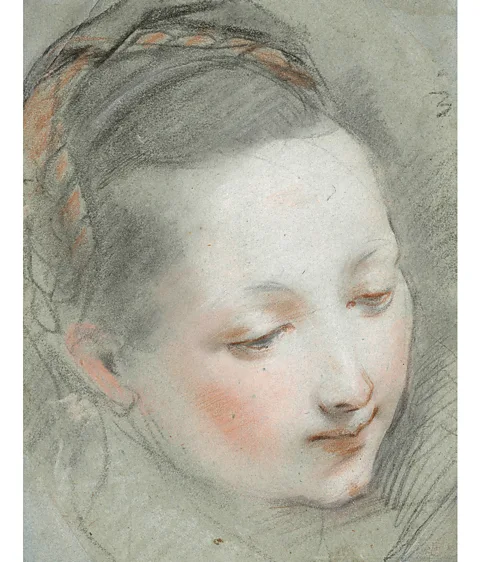

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection TrustIn Raphael’s The Three Graces, “beauty” means hairless, unblemished skin, and round breasts and buttocks as perfect as the apples the trio cradles to their chests. c1504-1505 Treatment of myth. When Sandro Botticelli introduced “Goddess of Beauty” in a vast tableau springthe flowing hair and transparent fabric emphasize the feminine softness. Pietro Ribery‘s post-Renaissance rendition of this subject (c. 1670-80) features the rosy cheeks and marbled bodies seen, for example, in the works of Federico Barocci. head of virgin (c. 1582), painted a century earlier and also on display in the King’s Gallery.

The rarity of female painters and patrons during the Renaissance meant that their work inevitably reflected the male gaze. “Perceptions of gender and the subordinate role of women in Renaissance culture were played out in images of men, especially portraits, that emphasized their social, political, and professional roles and status. “It was one of those times,” the historian says. author julia biggsExpert in Renaissance art history. “In contrast, the women in portraits of this period are primarily associated with ideal (youthful) feminine beauty, integrity (humility, humility, obedience), and maternal qualities. It is depicted.

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection Trust

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection TrustAs the apotheosis of charm, elegance and beauty, of Graces (Euphrosyne, Aglaea, Thalia), the daughter of the Greek god Zeus, whose Renaissance depictions reflected the male perspective of not only how women should look, but also how they should behave. Masu. They embodied this vague concept of elegance closely associated with Raphael, and patrons were keen to associate it with their own images. Although it was a term associated with distinction, mercy, and love, the circular dance of the Graces suggests balance and harmony, key principles of Renaissance aesthetics. As a group, they combine patriarchal precepts about female virtue with, perhaps unconsciously, a celebration of the female form and the sisterhood of the female bond.

At that time, female nudity had various meanings. Mr Biggs said, however, that the Three Graces “may have formed part of the metaphor of ‘virtuous nudity’, in which nudity was ‘an expression of sincerity and purity’. But in other regions, female nudity was “associated with shame,” he said. In Masacchio’s frescoes expulsion from the garden of eden (c1424-27), only Eve, branded with sin, has her genitals covered, but Biggs says: La scopa – Ritual humiliation of adulterous women in Ferrara, Italy – women were forced to run naked through the streets. ”

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection Trust

Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024/Royal Collection TrustSuch female nudity was in sharp contrast to the modest female dress code of Renaissance Italy. “In public, the majority of women cover their bodies from just below their collarbones to their ankles, and also cover their arms,” Biggs explains. According to Biggs, mythological and Biblical scenes gave artists an excuse to take off their clothes, and also to show the “erotic erudition” of their male patrons, or perhaps to “show homage to their sexual prowess.” “I want to do that,” he said. Even when the women are clothed, “Pictures of the Italian Renaissance” reflects the dichotomous roles available to them, like Annibale Carracci’s seductress. The Temptation of Saint Anthony (c. 1595) Thirteen different Virgin Marys by Michelangelo, da Vinci, and their contemporaries. However, this exhibition suggests that we cannot simply sit back and enjoy the Renaissance with all its prosperity and shortcomings. In place of the traditional catalog, we have installed an illustration sketchbook, and the gallery is stocked with art supplies. We are invited to participate in the work through our own creative efforts. Perhaps this is an opportunity to rethink the definitions of men and women.

Source: BBC Culture – www.bbc.com