Getty Images

Getty ImagesWritten by Giovanni Boccaccio in the 1350s, this collection of short stories deals with sexuality in ways that might still embarrass readers, and is now the subject of a Netflix comedy.

Quiz question: Which work is New Yorker Is it James Joyce’s Ulysses that is considered “the filthiest work in the Western classics”? After all, the novel was banned for being obscene. Lady Chatterley’s LoverIs it also prohibited? Or is it always a problem? LolitaNo, no, no, no. Not at all. What about the collection of short stories written in the aftermath of the Black Death in the 14th century? Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, written in Italian in the early 1350s, dwarfs any rival in spectacular salaciousness. It influenced the Italian language too, Boccaceco (which you can also say “Boccaccio-esque”) can be used to describe something obscene or lewd.

Netflix

NetflixWe’ll return to the bawdy stories later, but there’s much more to The Decameron than just its bawdy tales. In the preface to his magnum opus, Boccaccio writes: “My plan is to tell a hundred tales, or fables, or parables, or histories, or whatever you may call them, a hundred stories which, as you will see, were told over the course of ten days by a worthy company of seven women and three young men, who came together during the recent epidemic.”

Though barely mentioned after the first chapter, the plague forms the backdrop to The Decameron and gives the work a strange sense of horror. The opening sentences describe in relentless detail the horror as the plague sweeps Florence. Corpses rot in the streets and a kind of riotous debauchery begins as the social order is turned upside down. The constraints that had kept men and women in tightly regulated seclusion disappear as the home is destroyed. Outside, with no city hall officials to keep the peace, violent gangs ride through the town, plundering and howling. In the surrounding countryside, shepherd-less animals grow fat in the unharvested fields.

Why does this premise resonate?

This sudden disorder is the starting point for the new Netflix comedy series “Decameron.” The show’s creator, Kathleen Jordan, reflected on our own recent pandemic. To tell She wanted to explore “how the gap between the haves and the have-nots widens in times of crisis.” But in the turmoil of Boccaccio’s Florence, where rules and hierarchies loosen, Jordan also explores the possibility of reordering, where servants pose as mistresses and nobles become slaves.

The show’s premise is straight out of Boccaccio: 10 young aristocrats flee the horrors of Florence to weather the worst of the pandemic in a country villa outside the city, a lavish, sexy other world that’s fueled in part by the existential horror going on outside its walls.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut the Netflix series actually omits a core element of the original Decameron. As Boccaccio’s preface makes clear, his work is a collection of 100 short stories, linked by tales about young aristocrats spending their free time. Each day, when the sun is at its highest, they gather in the shade of a tree to tell each other stories, and each day a different member of the group takes turns being king or queen (essentially the host), who can impose a theme for the day’s story if they wish: a destructive relationship, for example, or a wife who plays tricks on her husband, or vice versa. One of the joys of Boccaccio’s Decameron is the way the different layers unfold: we watch them tell each other stories, making each other laugh, blush, complain, and then tell another story in response.

If this is Chaucer’s The Canterbury Talesyou would be right: Chaucer would certainly have read the Decameron. met Boccaccio borrowed several stories from his travels in Italy and fitted them into the mouths of his own characters: “Leve’s Tale,” for example, has the same bed-hopping plot as the tale told by one of Boccaccio’s young noblemen on the ninth day, while Shakespeare takes another tale of sexual mistaken identity from “The Decameron” (this time a woman who is tricked by a man in a darkened bedroom) and uses it as an “all’s well that ends well” plot.

It’s “equal opportunity” lasciviousness.

One thing that might surprise a modern audience is Boccaccio’s unashamed portrayal of female sexuality. There’s an equal-opportunity lasciviousness at work here. On the sixth day, as the group settles in for the afternoon, they are interrupted by a tremendous commotion coming from the kitchen. Two servants, Lisiska and Tindaro (one woman and one man), are having a heated argument. The topic is whether women are generally virgins on their wedding day. We don’t get to hear Tindaro’s side of things, but we do get to hear Lisiska’s. “None of my neighbors married as virgins,” she cries. “What about married ones…” The female nobles erupt in laughter at Lisiska’s uncensored tirade, but when Elissa, the queen of the group for the day, finally interjects, she deftly brings the servants’ argument to the men of the group. Who is right? The men unhesitantly side with Lisiska. “I told you so,” Elissa asserts.

Alamy

AlamyNo one seemed to have much doubt about the strength of women’s sexual appeal. Take, for example, the story told by one of the men on the third day: Masetto, a handsome young peasant, applies for a job as a gardener at a convent, hoping to get the chance to sleep with the nuns. To get the job, Masetto pretends to be deaf and mute, thinking that if people think he can’t chat up the young women, no one will object to his presence.

Instead, he finds that because he cannot speak, all the nuns, even the Mother Superior, are courting him, until he is worn down. Forced into hiding, he reveals what is going on to the Mother Superior, complaining that he does not have the strength to keep up with her appetite. The story has a happy ending, as the Mother Superior gives Masetto a promotion and puts him on a rotation to keep up with the demands of the convent in his old age. If you’re looking for a moral lesson, Boccaccio is rarely the best choice.

Of course, the nuns aren’t the only ones who can’t contain their desires. Before the third day was over, one of the women in the group responded with another story, this time about an abbess who was “very saintly in every respect, except when it came to women.” Full warning! The lascivious abbess is infatuated with a local beauty, but unfortunately her jealous husband Ferondo keeps a close eye on her every move.

So the abbot, with the help of the monks, drugs Ferondo and carries him to a cell in the monastery. When he wakes up, the monks tell him that he has died and been sent to purgatory as punishment for jealousy. The monks keep him there for nearly a year, beating and scolding him. Meanwhile, his wife pretends to be in mourning and secretly meets regularly with the abbot. Finally, the monks tell him that Ferondo can return to the world of the living if he reforms. Relieved and repentant, he returns to the village, again under the influence of a sleeping drug, where he spends the rest of his life as an ideal husband. His wife, on the other hand, never sets her eyes on another man again. With just one exception: “Whenever it was convenient, she was always happy to spend time with the abbot, who had so skillfully and diligently responded to her greatest need.”

Reading The Decameron, with its lecherous monks and badly behaved nuns, it quickly becomes clear that Boccaccio had little respect for religious authority. This caught the eye of the Church. When the Vatican first published The Decameron, Index of banned books In 1559, the Decameron was on the list. But that didn’t stop people from reading it. In fact, the public outcry against this attempt to suppress the work led to a compromise: the sexual scenes were left intact in the censored version, but the scenes featuring clergymen were rewritten and re-enacted as laypeople. Thankfully, this change didn’t stick, and modern translations retain all the irreverent splendor of Boccaccio’s original.

Getty Images

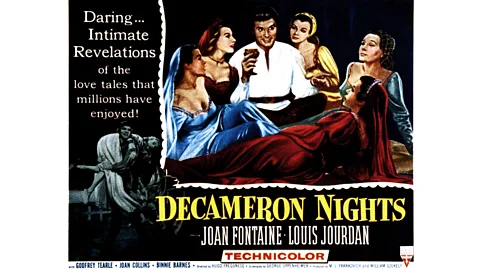

Getty ImagesWhen the COVID-19 pandemic hit four years ago, Boccaccio’s delightful text of The Plague went viral and was out of stock in bookstores. everyone Apparently he’s reading the Decameron. While the new Netflix series comes at the peak of this popularity surge, it’s not the first time Boccaccio’s classic has been adapted for the screen. Pasolini’s 1971 filmWhile the Decameron has held a loose resemblance to pornographic correctness, others have not, the best way to experience the expansive energy of the Decameron is to enjoy it on paper. Nearly seven centuries after it was written, these realistic, Boccaceco Stories still have the power to bring joy, comfort, and even a little surprise.

The Decameron is currently streaming on Netflix.

Source: BBC Culture – www.bbc.com