BBC

BBCEver since his 1988 debut The Swimming-Pool Library caused a stir, Hollinghurst has captured the hedonism of affluent gay men with both candour and literary elegance.

“He looks battered, but is smiling, / like an old seaman, nearly at rest. / A gold-haired boy twirls upside-down on rings.” These lines come from Alan Hollinghurst’s poem Isherwood is at Santa Monica, published in 1975 while he was reading English at Magdalen College, Oxford. The poem depicts one of his literary forefathers, Christopher Isherwood, author of such openly queer novels as Goodbye to Berlin (1939) and A Single Man (1964), watching a much younger boy playing on the beach. The imagery is evocative of the writer Gysrav von Aschenbach, dying in his deck chair as he watches the boy Tadzio on the beach at the denouement of Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella Death in Venice. As one might exclaim reading Hollinghurst’s latest novel Our Evenings, plus ça change.

Hollinghurst is now entering his 70s, with seven books that have rendered his name synonymous with gay British literature over the past five decades. His earlier novels, from his debut The Swimming-Pool Library (1988) to the Booker Prize-winning The Line of Beauty (2004), focus on specific moments in time, encircled by the Aids crisis, Thatcherism, and the prohibition of the “promotion of homosexuality” under the UK’s 1988 Section 28 law. His latest three books The Stranger’s Child (2011), The Sparsholt Affair (2017), and most recently Our Evenings (2024) encompass the scope of entire gay lifetimes. There is a sense of nostalgia, but often of anemoia too – a yearning for a time and a place one has never known.

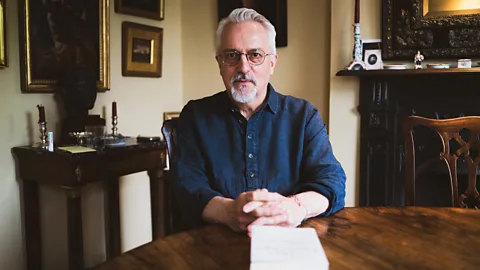

Adrian Cecil/ Macmillan

Adrian Cecil/ MacmillanHollinghurst, the son of a Gloucestershire bank manager, is an outsider, wandering through the affluent streets of West London and speculating on the revelries of the gay men who gorge on champagne and cocaine while talking of Wagner and Henry James behind closed doors. Reminiscing about how he used to walk down Kensington Park Gardens several times a week when he first moved to the capital in 1981, Hollinghurst once said, “it was all a part of my romantic sense of London as a scene of infinite possibilities, both real and fictional.” He translated that feeling of being outside, looking in, through Will Beckwith, the narrator of The Swimming-Pool Library, who comes of age in this entitled environ. And yet entering the smoking room of the Corinthian gentlemen’s club he reflects, “I felt like an intruder in a film, who has coshed an orderly and, disguised in his coat, enters a top-secret establishment, in this case a home for people kept artificially alive.”

His gay literary heritage

In 1979 Hollinghurst completed his Masters with a thesis on three of his favourite authors: Ronald Firbank, LP Hartley, and EM Forster. Following the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Britain in 1967, authors grew bolder with their literary depictions of relations and relationships between men – to the point that many suppressed the elegance of literary form under the need to hastily capture gay experience. The Swimming-Pool Library was a refreshing combination of style and sex, tracing the line of the male form in delicate prose with apparent insouciance. His imagery is lightly painted, but it is graphic in the mind – a technique learned from these earlier gay authors who could not, as Hollinghurst’s lesser contemporaries might, be blunt about sex.

Each of Hollinghurst’s novels might be subtitled as an ode to one of his literary heroes; The Line of Beauty to Henry James, and The Folding Star to Thomas Mann, for example. The Swimming-Pool Library is explicitly reverent of Firbank, an English author whose novels, including Valmouth (1919), were cited by Susan Sontag in her definition of “camp” due to their florid and humourous caricatures of the elite. Will reads Firbank voraciously in the novel, including a beautiful copy of The Flower Beneath The Foot (1923), which is symbolically destroyed when he is beaten up by a group of homophobic louts. The comfort and safety that being rich and educated often brings to gay people in the upper classes is not a constant, and occasionally ugliness mars the immaculate canvases with which Hollinghurst’s protagonists envelop themselves.

There are sanctuaries that recur: private members’ clubs, homes in West London or the country, Oxford (or sometimes Cambridge), and cultural venues. Opera and classical music drowns out the hubbub of the busy streets – in The Swimming-Pool Library Will attends a production of Billy Budd, an opera with libretto by Forster and Eric Crozier and music by Benjamin Britten. It is based on the novella by Herman Melville, about a sailor who is condemned to death for killing his master-at-arms, which is frequently read as homoerotic, as it is by Will: “The young baritone, singing with the greatest beauty and freshness, brought an extraordinary quality of resisted pathos to Billy; in the stammering music his physiognomy, handsome and forthright and yet with a curious fleshy debility about the mouth, made me believe it as his own tragedy.”

Will, like Hollinghurst’s other protagonists, recalls his sexuality burgeoning at Oxford. In Our Evenings, Dave Win recalls hearing from dons in their “stammering irrelevant way about Ancient Greece and relations between boys and older men”. It is reminiscent of Forster’s most obviously queer novel, Maurice, published a year after his death in 1971, in which the Cambridge student lovers at its centre learn of same-sex love through Ancient Greek writings such as Plato’s Symposium. It is an Oxbridge education which opens the door of these young men to sexuality as well as to the upper echelons of British society. Hollinghurst has said, “With the social world of public school types, these things are sort of accepted, particularly when you’re young, and in a way that they’re not when you’re out in the rough-and-tumble real world.” School and university exist in Hollinghurst’s world as a sort of playground of sexuality that becomes married to knowledge and taste.

His reflections on beauty

The Line of Beauty follows Nick Guest as he housesits for an Oxford friend whose father is a Conservative MP. His academic focus is on US émigré author Henry James, whose novels inform Hollinghurst’s perspective of outsiders becoming integrated into the elite, and the ensuing social dissonance. Nick is obsessed with his concept of beauty – derived from Hogarth’s theory about the “line of beauty”, a double, S-shaped curve representing the perfect form – which he draws across art, music, and the male form, rendering him blind to the behaviours of benefactors. Discussing James’s novels, Nick observes that characters often call each other beautiful when they are being wicked: “In the later books, you know, they do it more and more, when actually they’re more and more ugly – in a moral sense.”

Dave Win in Our Evenings is a slightly different proposition however. Talking to the BBC about the new novel, critic Caspar Salmon observes, “I don’t think this narrator completely meshes with the classic Hollinghurst viewpoint, which is apologetically classical and conservative, but animated by a desire to prod at everything. In the earlier books [it] is quite giddy, [but here it’s] more melancholy.” Dave is similar to Nick Guest in having been to Oxford and found himself in a higher class than that of his adolescence, but the crucial distinction is that Dave is not white. Race has been a complex theme in all of Hollinghurst’s novels, with his white protagonists’ narratorial gaze constantly falling upon men of colour described with fetishistic detail.

In The Line of Beauty, Nick apologises to a cab driver after a particularly nasty dinner guest called Barry Groom is abusive to him: “Nick’s heart went out to the Caribbean accent, in instant sentimental allegiance – he felt himself float out towards it from the cigar-choked huddle at the table, the Oxonian burble and Barry’s wine.” However, Dave in Our Evenings experiences prejudice directly, with one character observing that he is from Burma, “and the hint of a guttural r seemed to colour the country with her own unknown assumptions about it”. Dave needs to tread more carefully in his adopted social class than Nick does, aware of the unspoken judgements they pass. It is hard to imagine Dave, for example, having the boldness to ask Margaret Thatcher for a boogie at a Tory soirée, as Nick does.

Like Sally Bowles slowly feeling her hedonistic lifestyle in Berlin being encroached upon by the rise of Nazism in Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin, Nick Guest is for a while blind to the impact of political homophobia and the developing Aids crisis on his beautiful existence. The epigraph for The Line of Beauty captures the weight of his ignorance, quoting the King of Hearts at the end of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland deciding whether it is “important” or “unimportant” that Alice says she knows “nothing” of the business at hand in her trial. Like Alice, Nick falls down the rabbit hole from innocence to experience, in the space of four years, from 1983 to 1987.

Alamy

AlamyOur Evenings by contrast is the story of a lifetime, and Dave’s journey towards jaded melancholy is much longer. As critic Tim Robey tells the BBC, “I began to worry that Hollinghurst was becoming a bit of an ‘establishment writer’ in the novels following The Line of Beauty. A certain cosiness was creeping in. Our Evenings is a kind of recovery – it doesn’t feel cosy or complacent; it feels complete. It feels like an entire life is being reassessed and reevaluated for us.” Dave can never feel complacent amongst his more privileged peers due to his background, something demonstrated in an extreme fashion at the novel’s close.

The novel begins with a mention of Brexit, which may set alarm bells ringing in the British reader’s discourse-weary mind. Mercifully, it is more the casual announcement of a theme at the start of a symphony or opera quickly submerged by the rest of the orchestra and yet still ringing in the ears. It is a Wagnerian leitmotif, just as Aids is in The Line of Beauty, a chord that resonates all the more deeply through its underuse. As a student Dave recalls being taught about classical music by a don called Mr Hudson: “We must listen to it again, of course that theme’s been there all the time, half-hidden, hurried along, so that you can’t see its potential… Great tunes, sparingly used: that’s the secret”. Ideas of a Britain lost, crumbling Empire and now Europe, emerge in a smattering of references in Hollinghurst’s books such that they become his subject to greater degree than the aesthetic decorations of sex and sensibility.

“I think my relationship to Hollinghurst’s work has changed as I’ve got older, in roughly the same way as his protagonists – early on I read him for sex and dazzle, but now I think I appreciate his sense of queer lives shot through with grief or discomfort, odd fleeting moments of connection; his understanding of time and loss,” reflects Salmon. “His writing hasn’t diminished in its poetry. I may have fallen out of love with Hollinghurst along the way, but I have fallen back in love with him with this book, like an old flame,” says Robey. In Our Evenings, Dave reads an inscription on a sundial: SENSIM SINE SENSU, translated by his friend as “slowly, without sensing it, we grow old”. While Hollinghurst’s early novels feel more indebted to other gay writers, Our Evenings is of a style that can only be described as his own, rather than a rhapsody of a theme of Forster, Firbank, or James. With its broader narrative about the intensification of xenophobia and homophobia in Britain, the novel also stands as a warning to never lose sight of the bigger picture when focusing on exquisite, sensual minutiae.

Source: BBC Culture – www.bbc.com