Sky UK Ltd.

Sky UK Ltd.After witnessing the horrors of wartime, the photographer – now the subject of a biopic starring Kate Winslet, Lee – took up residence in the Farleys, an art-filled farmhouse in East Sussex. “The Farleys gave her the opportunity to heal,” her son Antony Penrose told the BBC.

The smiling, uneven face on the tile above the kitchen range looks vaguely familiar. Our guide confirms that it’s a Picasso. This historically fat-splattered piece of art in Farley’s Farmhouse, East Sussex, tells of frivolity, hospitality and celebrity friendship – all connected to the life led here by Vogue model-turned-war photographer Lee Miller and her surrealist artist husband, Roland Penrose. But there’s a deeper story.

Suffering from PTSD and an increasing alcoholism, Miller slowly rebuilt himself after covering the front lines and death camps of World War II – an experience portrayed in the film by Kate Winslet. LeeThe recently released biopic, which Starr also co-produced.

“It started out pretty shabby,” Antony Penrose says of the Farleys his parents bought in 1949. “For the first six or eight years, we had no heating. Our water came from a well, but it had so much iron in it that it tasted like tomato soup.”

Alamy

AlamyMiller threw herself into renovating the creaking 18th-century building and supplemented her friends’ post-war rations with food grown and raised on her farm at Muddles Green, near Chiddingly. She later became a gourmet cook and hosted famous friends (including a Miro doodle in the guest book) in her art-filled home.

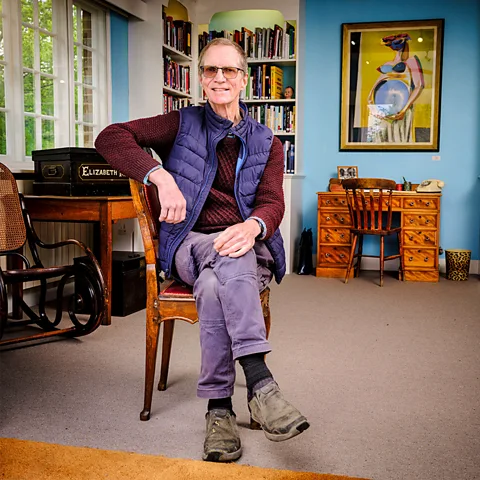

It was her final breakthrough in a multifaceted life. Farley’s House and Gallery He published a biography of his mother, The Life of Lee Miller, as a museum and archive, and the film Lee is based in part on his book.

Born in Poughkeepsie, USA, Lee Miller was “discovered” as a model when Conde Nast pulled her off a road in New York City, and she became a frequent feature thereafter. Vogue.

Roland Penrose/Lee Miller Archive

Roland Penrose/Lee Miller ArchiveA 1920s advertisement for Kotex hygiene products, featuring Miller’s image, hangs on the wall of Farley’s lounge. Fashion houses were so shocked that they no longer wanted to model her dresses., But the unconventional Lee laughed off the scandal and was soon behind the camera, and with her usual audacity she arrived unannounced at Man Ray’s studio in Paris as an apprentice, and the two (who would later become lovers) developed a technique for solarizing in the darkroom.

Lee started out running a portrait studio, then began photographing fashion and other subjects with a keen eye for surreal contrasts. After a short marriage, she went to Egypt. Then, as the war raged in Europe, she obtained a US military press credential and became one of the few women correspondents. She persuaded Vogue to revamp its editorial policy and publish stories she had personally covered.

Our guide at Farley’s shows us the knuckledusters Miller wore for protection — “bronze by day, silver by night,” Miller jokes, wryly describing his glamorous early career. His cookbook-lined study features German binoculars, and on the wall is a photograph of Miller disdainfully bathing in Hitler’s Munich apartment, his boots soiling a mat with the mud of recently liberated Dachau.

These loot items were not exhibited during her lifetime – Miller’s wartime experiences were so forgotten that Antony, born in 1947, only found out about them after his mother’s death, when his wife discovered the shocking photographs and reports in the Farleys’ attic.

Miller stayed in Europe, continuing her reporting for a few months after the release, before joining Rowland in London. After Anthony’s birth, she moved on to new challenges at Farley’s, where the kitchen became her base.

Tony Tree/Lee Miller Archive

Tony Tree/Lee Miller ArchiveThe couple’s housekeeper, Patty Murray (who later regularly polished Picasso’s tiles), had “endless chores”, Mr Antony told the BBC, while Mr Lee was a “flashy character” who would fly in from London at weekends and arrange for a gardener to deliver piles of vegetables.

“Food rationing continued until 1954, so our first five years at Farley’s were spent cooking frantically and transporting loads of food to London to distribute to friends,” Antony explains. “It was really important to my parents to have vegetables. They killed and butchered pigs, then tried to get milk and make butter, cheese and so on. It was really important to Leigh. She used all her skill and ingenuity to feed people.”

He now understands the driving force: “She had witnessed the most horrific scenes of mass starvation you can imagine. She had been present at the liberation of four concentration camps where people were more skeletons than people. I think that resonated with her deeply. She was very concerned about people’s well-being in general and about feeding people in particular.”

Alamy

AlamyLater, in a more carefree period, Lee took advanced courses at Cordon Bleu and fell in love with creating complex, surreal dishes (her always-provocative repertoire included cauliflower breasts smothered in pink mayonnaise).

Working Guest

Piles of half-used spices, not often found in a mid-20th century British kitchen, still sit on her shelves, and a Picasso ink drawing inspired by a farm bull hangs above the table where she and other friends once helped chop vegetables.

In fact, Lee’s final photo essay for Vogue, after a fashion shoot in his hometown’s village, was humorously titled “The Working Guest.” Produced at Farley’s in 1953, it features images of New Yorker cartoonist Saul Steinberg wrestling with a hose, MoMA director Alfred Barr feeding pigs, and Henry Moore adjusting a sculpture that once featured among the garden’s many artworks.

At mealtime, guests gather in the yellow-walled dining room, decorated with paintings by Rowland and his Surrealist contemporaries, but most strikingly, the large fireplace is covered in a fantastical mural inspired by the “Long Man of Wilmington,” a chalk-painted figure on the nearby South Downs.

At times, the tables were decorated with silver-plated King Kong ornaments, spoiling the mansion’s fine centerpieces — fun details that Anthony said visitors should note around the house.

Farley’s certainly has a wide variety of items on display in its vibrant blue hallways: among the many items on display are terracotta figures from Tenerife, iconic sculptures from Scotland’s New Hebrides, a mummified rat (discovered under the floorboards), an advertisement for salt cod, and a badger skin.

There’s nothing flashy or hierarchical about it — hand-painted plates by Picasso sit on a dresser in the dining room alongside kitschy junk-store finds that caught the couple’s eye — and the whole place exudes warmth and humor.

Alamy

AlamySo did Miller find peace there? “I don’t think there was anything magical about being at Farley’s,” his son recalled. “I think it gave Lee the opportunity and the motivation, the impetus, if you like, to heal herself. She loved the place, she wanted it to be a comfortable place – what she called a ‘big barn house’ – and she loved entertaining.

“For her, it was kind of a challenge,” he added. “She was very resilient in the practical sense, very resourceful. It was therapeutic for her. Not therapeutic in the sense of sitting under an apple tree and contemplating nature.”

Alamy

AlamyWinslet has a penchant for playing “bold” characters and “down-to-earth” personalities, and Antony had his eye on casting her as the mother long before the film was even conceived. Once attached, Winslet was so passionate about telling Lee’s story that she spent years helping raise funds. While on-set filming was limited to establishing shots, Winslet naturally spent time exploring the Farleys and their archives. Like many famous creatives before her, she Photographed For vogueing at the kitchen table or in the garden.

Next autumn, Tate Britain in London will host the country’s largest Retrospective Antony hopes that the film, and the upcoming biopic, will help him and his daughter Ami Buhassan continue their efforts to bring greater recognition to Lee’s extraordinary life and talent.

“[Originally] “People saw her as a strong muse for Man Ray, Picasso and Roland, but we started to push back against that because it made her seem very passive,” he explains. “She wasn’t just beautiful, she was an active agent in her own right, going out and exerting herself and making things happen.”

Source: BBC Culture – www.bbc.com