Debating our differences unites us more than anything else. Many issues divide Americans: economic policy, social policy, foreign policy, race, privacy, national security. Partisan districting and exclusive party primaries exacerbate these divisions. Our former president was nearly assassinated shortly after saying at a rally that “our country is going to hell.”

People still say that if we get along personally, we’ll get along politically. Polarization is often associated with interpersonal tensions. But reducing emotional divisions doesn’t make much difference politically. Support remains strong no matter what parties do, including behavior that is personally reprehensible. Parties and their opponents are mimetic rivals, imitating each other’s behavior while creating another reason to boast about their own integrity. Each side can say, “It’s insanity to respect all norms while the other is doing vile things.” As in the playground counterattack, “He hit me first.”

Voters are not so much driving polarization as they are being driven by it. Candidates and parties adopt polarization strategies to win elections and claim to represent the electorate. Moderates are the losers and even their attitudes are negative. The average voter is not as divided as the leaders, but they are silenced by money and power and have no other choice.

Political violence stems from psychological issues, dangerous rhetoric, and stubborn mindsets, but ultimately from a widespread distrust of institutions like big business, schools, the news media, government, the judiciary, and organized religion. An elite political and economic system alienates many Americans, and increasing diversity threatens their social status. Those with low self-control and aggressive tendencies turn to violence, while those who are successful blame the country’s problems on the less fortunate or government interference. Americans no longer simply disagree; we live in a different reality.

Emile Durkheim, the “father of sociology,” argued that our differences, not just our similarities, bind us. Although he focused on the industrial societies of his time, he believed that the social disruptions caused by economic inequality were temporary. Today, scholars popularize his ideas, calling them “transformative solidarity,” in contrast to exclusive in-group solidarity. Transformative solidarity brings unlikely allies together on common ground to address shared problems, building trust and a sense of control.

Real-world examples include conservative religious groups and gay activists working together on the Respect Marriage Act, bipartisan efforts on the Americans with Disabilities Act, and people across the political spectrum taking active role in climate change and using sharp differences to their advantage.

Political polarization began at the nation’s founding and has developed over time. It may continue to do so. There are no one-size-fits-all solutions or easy answers. But a focus on action over agreement can turn opponents into allies. In the wake of the Ohio train derailment and pollution disaster, vice presidential candidate J.D. Vance, a critic of clean energy, worked with Democrat Sherrod Brown to pass the bipartisan Rail Safety Act of 2023. Vance said, “I don’t know if this is going to be a model, but [but] I hope so, because I certainly want to get more done.” Safety transcends partisanship. Or… did conviction mask opportunism? What else is new?

What is new, as many see it, is Vance’s rise as a leading symbol of right-wing populist authoritarianism, known for taking extreme positions. The media denounces him for his reliance on celebrities for financial gain and intellectual prestige, and for his ability to outdo his boss’s rhetoric. But this criticism misses the point: it overlooks Vance’s true passion for leading the party toward a more astute populist agenda and for making social conservatism “not just about issues like abortion, but a broader vision of political economy and the common good.” These issues will not go away with a mere personality change. The “us vs. them” mentality resonates with the deep-seated anger and confusion of millions of people. Promising results may come not from policy debates and solutions, but from practical actions like those mentioned above: solidarity in action, building consensus, and perhaps mutual respect.

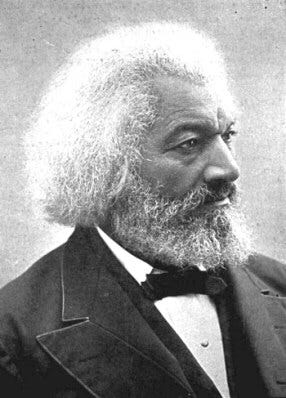

History offers another example of how agreement and mutual respect continue to evolve, albeit from different angles. During the American Civil War, former slave and politician Frederick Douglass addressed outraged Northerners who opposed slavery in the South and wanted to break up the Union. He rejected their motto, “No Union with Slaveholders,” and offered an alternative:

“As an expression of hatred against slavery, the sentiment is good, but it offers no clear principles for action, and illuminates no course of duty. It leads to false doctrines and pernicious consequences. To dissolve the Union in order to put an end to slavery is like burning a city to drive out thieves. We hear the slogan, ‘No Union with Slaveholders.’ I answer with a wiser slogan, namely, ‘No Union with Slaveholders.’ Slave ownership“I will unite with anyone to do what is right and I will not unite with anyone to do what is wrong.”

Personal anger and indignation, however justified, exacerbate the injustice they lament. The issue was the abolition of slavery, not moral indignation or rage. Douglass urged abolitionists to remain committed to the institution they despised, for only then could it be overthrown. The future was in their hands.

Frederick Douglass stands out among all the things that divide us.

Notes and reading

[*] “It is not at all superstitious, and it is even realist advice to prepare for and expect “miracles” in the political sphere.–Hannah Arendt, The Crisis of the Republic: Lies, Civil Disobedience, and Violence in Politics, Reflections on Politics and Revolution (1972), Chapter 3, “On Violence”

in The Human Condition (1998), In Action 238-247, Arendt writes:

“New things always arise against overwhelming odds. In the words of natural science, it is ‘an infinite impossibility that occurs periodically.’ … Unpredictability is the price of freedom.” Arendt says that “orthodox political thought” ignores the secular importance of Jesus’ teachings, and compares them to the “originality and unprecedentedness” of Socrates’ insights.

“We use our imaginations Instead of running away from the world, we join it.” Iris Murdoch, Sovereignty of Good (1970, 2001) – Chapter 3, “The Primacy of the Good Over Other Concepts”

“As a mere expression of abhorrence to slavery…”Frederick Douglass said this in his speech, “The Emancipation of the West Indies,” delivered on August 3, 1857, in Canandaigua, New York:

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of FreedomDavid W. Bright (2020) was named one of the best books of the 21st century by The New York Times and won the Pulitzer Prize for History.

For the concept of “transformative solidarity” and excerpts from Douglas’ speech, see Solidarity: The past, present and future of world-changing ideas Leah Hunt-Hendrix and Astra Taylor (2024), pages 302-304.

“Emile Durkheim argued that our differences, as well as our commonalities, unite us.” – Division of labor (1893, 1997) Chapter 2, “Causes,” and Chapter 3, “Effects.”

“New research suggests that individual solutions can drive systems-level change” “Overcoming polarization on climate change” – Dominic Packer and Jay Van Bavel, Our Power (Newsletter July 2024).

“Why the Left Gets J.D. Vance Wrong” – Zaid Jilani compact (July 17, 2024) vs.J.D. Vance is selling his soul. He has plenty of buyers.” Ed Simon The New York Times (July 17, 2024).

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895)

American social reformer, abolitionist, speaker, author, and politician who became the most important leader of the African-American civil rights movement of the 19th century.

Source: 2 + 2 = 5 – williamgreen.substack.com